“Wow, your accent is so impeccable! How long have you been learning English?”

“You must have so many doctors in your family, I’m sure it is easy for you.”

“Do you really want to become a doctor? Or is it just because your parents are forcing you to do so?”

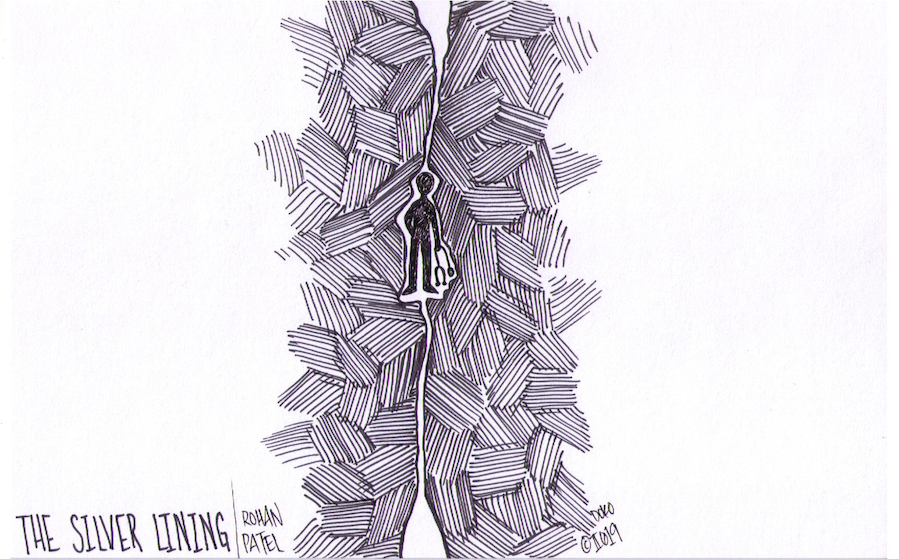

For the people who never believed I could.

For the people who find my worth overshadowed by the color of my skin.

For the people whose innocent questions slowly tear my spirits down.

This is for you.

So often I lack enough energy in my body to fight these battles. No matter how warm my personality is, no matter how much knowledge I gain and demonstrate, no matter how prepared I am — it seems as though I am hitting a ceiling. But what are those barriers that seem too tall to overcome?

While walking through the bleak halls of the maternity ward, my classmate and I were rehearsing our checklist of questions used to better understand our patient’s status: bowel movements, pain tolerance and associated symptoms. Interviewing patients has become second nature to me at this point. It’s a special task that it allows us to assess patients’ ailments while providing a comforting presence to ease their mind. My classmate began the conversation with our patient, and we tag-teammed through the rest of the interview.

Unfortunately, I left the room with a vague sense of failure even though we got to the bottom of our patient’s complaint. Throughout the encounter, it almost seemed as if I was a ghost, an unwanted entity. My classmate completed the interview comfortably, but the patient did not once make eye contact with me and was reluctant to provide any answers to my inquiries. Similarly, she would not let me perform any part of the physical exam on her, while the other student completed the physical exam without issues. A sinking pit in my stomach began to grow, while the dread loomed in the back of my head.

Why wouldn’t the patient answer me? Why did she make me feel so insignificant? A six-letter word started to formulate in my head, blaring like the flashing billboards in Times Square. Racist. But somehow, that word failed to accurately fit what had just happened. I mulled over the interaction repeatedly to identify what I did wrong. The more I thought about it, the more my mind realized that this situation was far more subtle than I had initially imagined. Curious to see if I misread the situation, I approached my classmate about it.

“Don’t you think you’re overreacting? I didn’t think anything was off,” my classmate countered.

And there it was again. The rush of shame and anger built up and heated my face, leaving me beet red. I realized it was a losing battle. How many years of this invalidation could I possibly handle, when my white counterpart was never forced to endure these moments? Then it came to me: the reason I felt ignored, the reason for the anger that built up in me, whose name evaded me until that moment.

Microaggressions! Subtle, common verbal and non-verbal communications that create a hostile environment for marginalized people. Whether or not these slights are intentional, microaggressions flood medicine’s daily activities and haunt our workspaces. People of color are all too desensitized to these behaviors, which vary from colleagues making passing comments about our culture, language, or speech to the biases that medical research has against marginalized groups.

It can be easy to forget how covert racism has been plaguing the professional world for decades. As a South Asian, these microaggressions are often masked under undertones of polite comments and praises. The disparities that the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community face are built on the model minority myth. Our individual problems are seemingly insignificant compared to the great “advances” the AAPI community has made in America to achieve the American dream. Within our community, though, inequalities are ever-high.

There are huge gaps in the literature regarding how these microaggressions affect people of color at all levels, especially for medical students. More medical schools are pushing for diversity in their student bodies, yet many groups continue to be underrepresented in medicine. Cultural competency courses are not implemented heavily in our core curriculums and are usually relegated to less than an hour of coursework over the entire four years of medical school. And how often are women of color in positions of leadership in medicine? Many say that medicine leans heavily on “tradition,” and they are right. But is this the right way?

Microaggressions have always been present, and some traditions in the medical field continue to reinforce them. But this does not mean that we need to continue those long-standing practices for generations to come. When a professor does not believe we have the leadership skills to take charge, we must show them. When an attending thinks that we should not speak up about our issues, we must tell them. When a colleague does not understand how our culture shapes our perspective and medical care, we must teach them.

We are the future leaders of the medical field. Our differences make us valuable members of the team; after all, medicine is a profession of collaboration. Sharing our own cultural backgrounds with our peers helps build their overall cultural sensitivity, allowing all of us to better provide care for a diverse variety of patients. As we break down these barriers that prior generations have constructed, new traditions will be born. My brown skin may be on display for all to see, but it is my attitude and my fortitude that will break through that white ceiling.

From the outside, medicine is a grand profession — physicians and trainees work together to help those that are in need while saving lives. However, every day we are faced with darkness that does not get shown to outsiders. How we deal with these obstacles truly shapes our experiences within this profession, often leading to physician burnout. This column will focus on some of Rohan’s personal experiences facing the dark sides of medicine, while shedding light on how one can overcome these challenges. After all, there is always a silver lining through the darkness.