“Time of death: 12:26 p.m.”

Hearing those words on the first day of my intensive care unit (ICU) rotation was surreal when just a few hours ago we were discussing the patient’s status during rounds.

That morning, my attending informed the ICU team that we should be preparing for the worst for this patient, as do not resuscitate (DNR) status was established per the family’s recommendation. I hadn’t realized it would be this soon.

Being in medicine, I am frequently numb to the idea of death, and my emotions are walled off from my professional identity. To me, feelings are often overpowered by the volume of work that requires attention. As I passed by that patient’s room, I noticed that it was dark inside and the curtain was closed, with the soft sound of sniffles heard just beyond the barrier. My brain had no time to fully interpret that information before my resident beckoned me to see our newest patient.

John Doe: unknown male, unknown age, coming in from the field due to a possible overdose, coded once in the emergency department and transferred to the ICU. We tried to work as fast as possible — drugs, oxygen and a plethora of maintenance. When he seemed fine enough, I was whisked off to another task on another patient. After all, my resident and I had seven ICU patients to take care of; there was no time to fixate on any one. I was so frazzled by the endless avalanche of items to check off the list that I was relieved when it was finally time for the medical student lectures — even though it was only day one of my rotation.

When I returned to the ICU after lectures, things seemed to have settled down. All the patients were tucked in, all appropriate workups were completed, and the resident was enjoying her few minutes of restful peace. Lost in my thoughts, my eyes passed over the telemetry monitors. The monitors tracking the heart rate are always beeping; the patient in bed 10 was bradycardic, and another in bed 22 had some a-fib. Once again, I found myself indifferent to these sounds that signify life. A moment later, a red blaring word caught my eye — “asystole.”

Often, nurses remind us that patients constantly knock off their leads so that their rhythms cannot be properly read. So, thinking this was misread, I casually approached bed 14. I peeped inside to see a frail man lying still, sleeping. He was peaceful, almost as if in a trance. I glanced over at the monitor which confirmed the flat line. Alarmed, I informed the nurse and we both entered to check if there was a need to replace leads. To our surprise, the leads were in place. The nurse instinctively checked for a pulse.

Pulseless. How long? Why did no one know? The nurse yelled to call a code and immediately began chest compressions. Some nurses did not bat an eye while some seemed surprised we were even calling for a code. I reiterated to call a cardiac arrest (Code 99), and soon over the announcement system, the entire hospital was booming with the announcement of what we had found: “Code 99, fourth floor ICU. Code 99, fourth floor ICU.”

My adrenaline began pumping almost as if to make up for his non-pumping heart, and I was invigorated to be of use in this patient’s revival. I started a round of chest compressions as the code team arrived. A beautiful display of collaboration was in play during the code — the entire team of doctors, nurses, pharmacists and respiratory therapists choreographed to resuscitate the patient. Each team member was rapidly falling into their roles like the pieces of a puzzle, communicating and displaying their strengths while utilizing their skills to the maximum.

Ten minutes into the code, I heard the announcement system again, shouting, “Code 99, fourth floor ICU.” It struck me as odd that the announcement was repeated so late, given we all heard it at the beginning of the code. A nurse ran to our room asking for help at bed 17. My heart dropped. The code team quickly realized that there was another simultaneous Code 99, this time being my John Doe.

At that point, we split in half; one code team properly trained to focus on one Code 99 was spread thin across two patients simultaneously. Without the strength of a complete team, chaos ensued. I continued helping on the first code. Shortly thereafter, I enjoyed a sigh of gratitude because my current patient’s pulse returned.

Without taking another breath alongside the resuscitated patient, we all rushed over to John Doe to assist. The code team was reunited. Unlike our older patient in bed 14, we had no information on John Doe. So, we started by going through the ACLS protocols to identify the cause of his cardiac arrest. Not more than 15 minutes into assisting with John Doe, a nurse asked for the team to immediately return to our old man in bed 14, whom we had just stabilized not ten minutes earlier. Overhead confirmed yet another Code 99, and the code team split again.

At this point, those assisting in chest compressions were drenched in sweat, flushed bright red and physically drained. Our minds were fatigued and split between two rooms, precluding us from working at our best. John Doe thankfully regained a pulse 38 minutes into his code. But it seemed that both patients were teetering on their last breath, as were we. Bed 14 continued to crash with all resuscitation efforts temporarily successful only for his weak heart to fail just a few minutes later. John Doe ended up on the maximum dose of vasopressors, and without any family or friends to contact, we were clueless as to what his wishes would be.

The disarray endured while the team was rapidly trying to make a final — and I mean truly final — decision on John Doe. The code team worked on the two beds for two hours until, at 4:24 p.m., John Doe was pronounced dead. 23 minutes later, tears of sorrow and loss emanated from bed 14 as we pronounce the old man’s time of death at 4:47 p.m.

A classmate also working in the ICU and I left a bit jittery and exhausted from the day’s events. Throwing a few jokes at each other, we tried to communicate: “If one more thing goes wrong, like if someone honks at me or cuts me off, I’m just going to lose it!” My mind was unable to focus on anything related to medicine; it seemed as though the mental exhaustion was manifesting itself in a pounding headache to match my sore muscles.

We parted ways with partial smiles. My normally pleasant nature was working as hard as I had during the day to cover up something. I struggled to shake off the feeling of something dark growing in me. As soon as I exited the hospital doors, the darkness imploded and I broke down. Bawling, I rushed over to the train to quickly get home to my safe space. But the despair was so great that I needed to veer off to a deserted street to simply cry it out.

I was sad for my three patients. I was heartbroken that John Doe, who should have been a resilient young man, passed so early without saying goodbye to anyone. I was devastated that the families lost their loved ones. I was furious at myself for not being able to do more for my patients. I was resentful that even a large team of medical “professionals” could not save these patients. I felt hopeless that my position as a future physician seemed to have no meaning in the care of these men. I was disappointed that I was not excited to return to the ICU the next day.

After collecting myself and my thoughts, I sought counsel from the only one who could slap some sense into me: my best friend. She gave me permission to grieve for my patients. She reminded me that this grief demonstrates that I care about those that I take care of, and that they are not just a collection of symptoms or diagnoses that I am trying to fix. She reiterated that being vulnerable is not a sign of weakness, but rather a sign of strength, especially in the medical profession. She encouraged me to let out my emotions; this is the best way to confront the strife that we go through. She told me to keep working hard and that I am doing my best — that is all my patients could have asked for.

—

Grief is a profound response to loss that we experience on the wards as medical students, but we rarely discuss the hardships. We can be stricken with imposter syndrome, feeling so insignificant in the course of a patient’s care that we believe we had no impact on their lives. And when faced with a patient’s death, we often don’t feel warranted to grieve. We sometimes detach ourselves and treat these humans beings like just another patient vignette on a never-ending test.

But we are significant players in our patient’s care. As medical students, we connect with our patients when our residents do not have time to. We learn about their histories, their concerns, their beliefs, and their desires; we learn about who they truly are beyond the hospital room. When our patients die, it is understandable that we feel grief.

Finding ways to support ourselves physically and mentally is the key to our stability. We are physicians-in-training, but we are also humans with a very real set of emotions. So, as medical students and simply as people, we need to normalize the grief that comes with our work. After all, grief on the wards is inevitable.

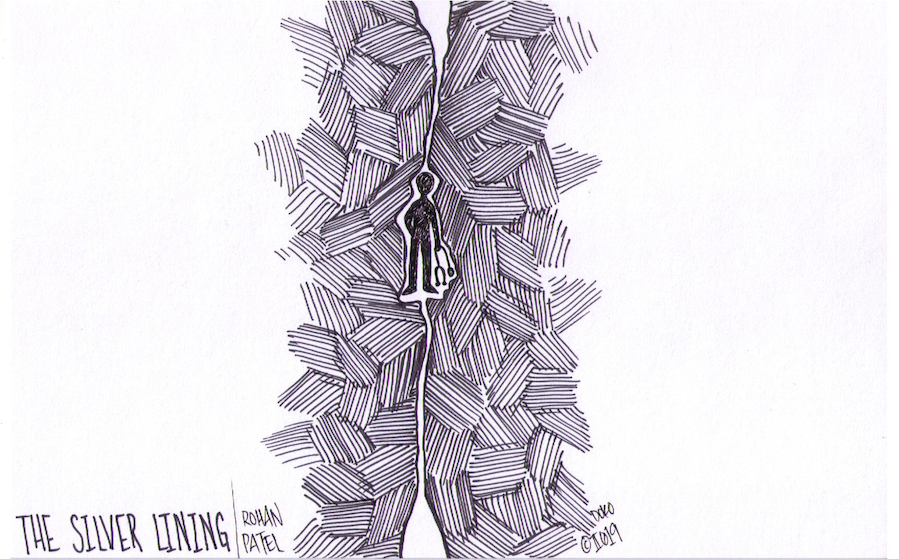

From the outside, medicine is a grand profession — physicians and trainees work together to help those that are in need while saving lives. However, every day we are faced with darkness that does not get shown to outsiders. How we deal with these obstacles truly shapes our experiences within this profession, often leading to physician burnout. This column will focus on some of Rohan’s personal experiences facing the dark sides of medicine, while shedding light on how one can overcome these challenges. After all, there is always a silver lining through the darkness.