For me, the start of medical school was a never-ending paradox: I felt excited and terrified, accomplished and unsure, ready and yet wholly unprepared.

At the beginning, much of my fear and doubt derived from the sudden shift in my career. I entered medical school after receiving my B.A. in English and teaching high school English for two years. Despite what some of my medical school interviewers implied, medical school was always “The Plan,” and I wasn’t overly concerned that my interest in Romantic poetry would somehow limit my ability to learn neuroanatomy.

Instead, I was worried that medicine would consume me only to regurgitate me as a mere collection of cells and systems — just like those I would be expected to regurgitate on the test. I was worried that the demands of knowing it all would make me believe that I could know it all, that there is nothing in the spaces between what we know. I was worried that bathing in science would make me stop believing in art.

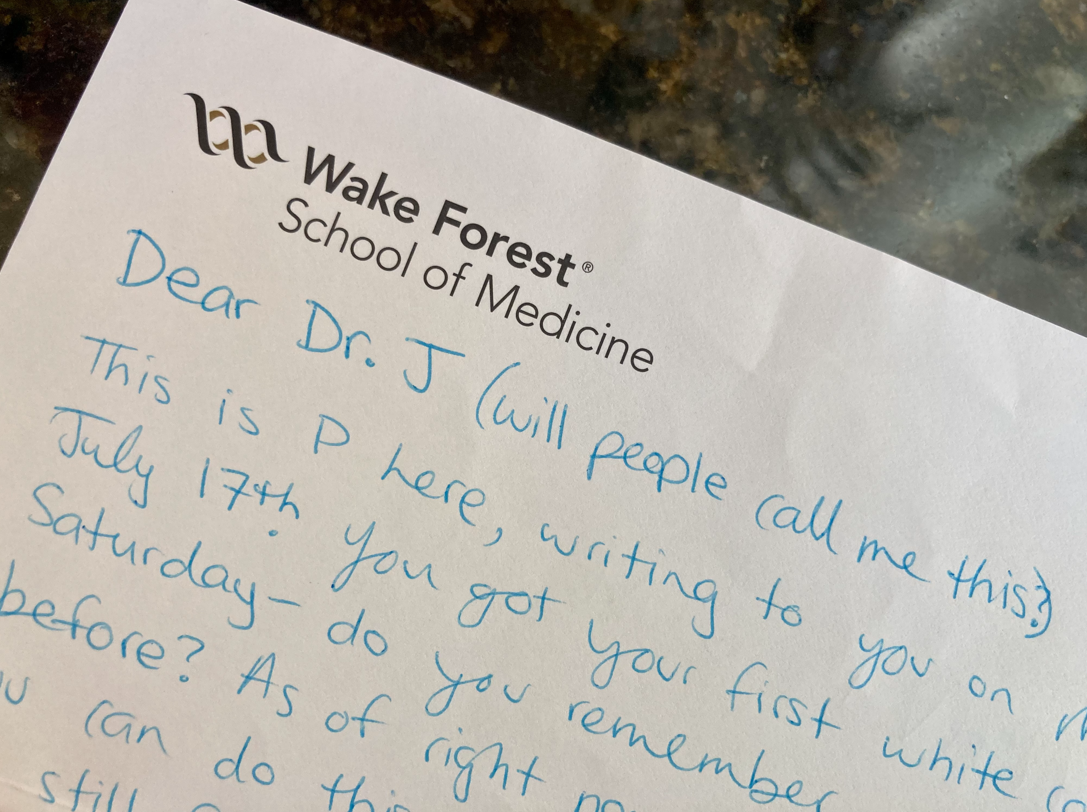

When I graduated, I received a letter that I wrote to myself in the first week of school. In that, I confronted my fears:

“Remember that you’re here to learn the tangible skills and knowledge necessary to serve patients and people. Remember that you’re a reader, writer, and thinker — doctor should only magnify those. […] Whatever it is that you’ve decided to pursue, I hope that you’re fulfilled, that you made friends, that you’ve maintained your family, and continued to love limitlessly. Stay energized by language and find joy in creativity.”

After my first year of medical school, the process of consumption was nearly complete. And I wasn’t feeling magnified or fulfilled or energized; my love seemed to have limits. So, I sought out the therapist who is employed by the school to respond to our inevitable ebbs. I nervously crept into her office as if my struggle was an unprecedented secret. I planned to talk to her about the workload and the pressure. But somehow, I spent an hour telling her about my senior thesis on Percy Shelley and “Mont Blanc” and Romanticism and skepticism and faith. She listened to me catch fire, and she restated what I had already written to myself (and seemingly already forgotten): language is food for my soul.

So, I went home and Google searched ‘medical student writers.’ This is how I found in-Training. I made an inquiry on the website. I wasn’t sure that I had anything to say, but I desperately missed the intimacy of writing. The publication brought me on as an editor that summer. The next year, I became co-managing editor, then co-editor-in-chief the year after.

At the end of medical school, looking back, it is clear to me that my investment in in-Training over three years was an investment in myself. The existence of the publication permitted me to exist as a reader, writer, and thinker — as well as student doctor. The virtual space was a reminder that creativity matters and joy matters; the people who I worked with were a reminder that I am not alone and don’t have to be. Together, we believed in science and art and scientific art and artistic science. We embraced paradox.

At the end, in-Training was my way of doing what I set out to do in that letter from the first week of medical school.

Image credit: Photograph provided by the author.