Did you know doctors can sew your cervix together to keep a baby inside? Isn’t that strange?

When I was 17, I went to the gynecologist for a Pap smear because my mom said, “Once you have sex, you have to get one.” It felt like punishment, but it was also the only way I had a chance of getting birth control. I went to three different doctors and, exam after exam, they kept saying I could have cancer. I had a ‘colpo’ — whatever that is. After that, they did three different procedures on me (three!), all to take pieces of my cervix.

I don’t remember what they were called or what even happened. All I remember is the pain.

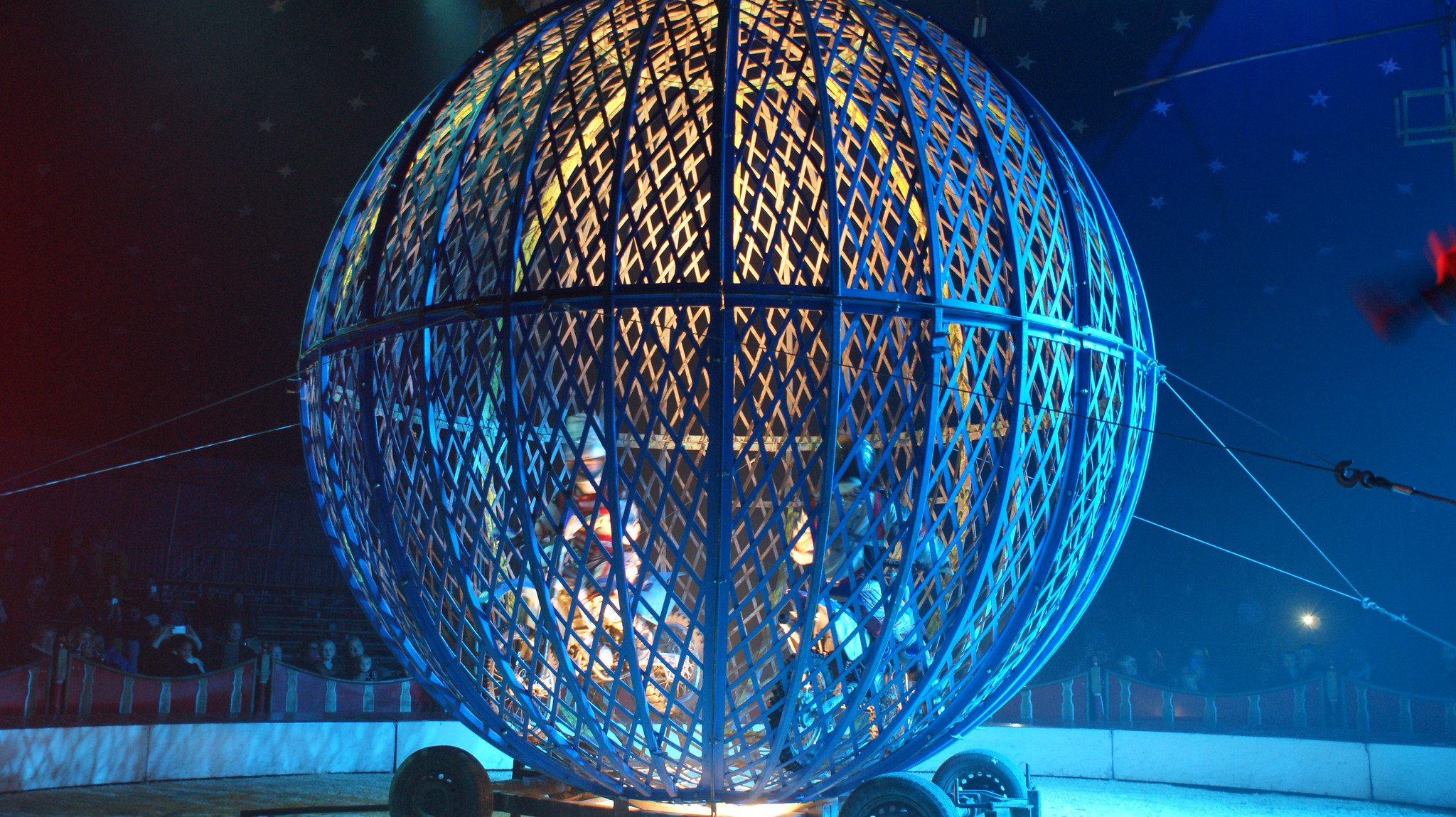

My gynecologist retired. When I got a new doctor, he brought all of his colleagues in to look at my cervix. Person after person came in to look down there — no one looked at my face. It made me feel like a zoo animal. I didn’t feel like a person, and I don’t know if that makes me feel better or worse. Finally, he talked to me directly and said my cervix looked like a Picasso painting of what a cervix should look like. He used words like ‘gaping’ and ‘scarred.’ He told me that no doctor should have ever taken pieces of my cervix because I would have likely cleared the cells, no problem.

He told me all of this pain and embarrassment and sacrifice was for nothing.

I tried an IUD for birth control, and my body expelled it within hours. He called my cervix ‘incompetent.’ Essentially, my body wasn’t doing what it was naturally made to do because of procedures that may have never been necessary. He told me he would likely have to sew my cervix together if I ever wanted to have children.

Did you know they can do that?

I share this patient story because I have heard many similar experiences from women who were young gynecological patients in the time when the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) preventative recommendations were going through major changes. This patient is not a medical professional. She is unfamiliar with colposcopy, biopsies, cerclage, etc. That stuck out to me most — she remembered the feeling of suffering so distinctly but none of the details leading up to it.

In medicine, we emphasize evidence-based practice, and that evidence is often changing. Although our patients benefit overall from these discoveries, there are always those who suffer in the interim like this woman. In practice, we will always be faced with this balancing act: What is the most cost-effective age for screening? What is the least invasive, most specific next step in diagnosis? Is there a chance the harm outweighs the benefit?

I share this story because like the process of cerclage, her narrative is cyclic, beginning and ending with the same seemingly lighthearted question used to mask and possibly help her cope with the underlying tragedy. I share her story because I believe it and those of similar experiences deserve to be heard. I hope you hear her story louder than my response to it. I hope you hear a story of affliction, vulnerability and courage. I hope it encourages someone to listen. After all, if we do not first hear our patients, then how will we begin to help them move forward?

Image credit: Cirque Maximum (CC BY-SA 2.0) by DaffyDuke