Editor’s note: Over the next five weeks, we will be featuring a series of essays by Kate Crofton on anatomy lab. Her essays are based on 27 interviews with medical students, faculty, clinicians and donors.

We are thrilled to bring you the introductory essay for the series. Read the second installment of the series here.

Dedicated to Table 22.

You gave us your house,

and our hearts were at home.

I am a dam ready to burst, my walls at the limits of their capacity to hold back any more pounding water. I narrowly escape failing the first anatomy exam of my first year of medical school and consequently am required to meet with the course director to discuss my academic performance. She asks how anatomy lab is going for me, and I tear up immediately. She inquires: is it affecting the rest of my life in any way? Influencing my appetite? Impairing my ability to sleep? Yes. It has a hold on every aspect of my life, but I have been too focused on pushing through to really come to terms with its impact. I stumble back home, eyes awash in tears. The floodgates have been forced open, and I begin to feel a release.

Looking back, I can see that I was lost. Lost in a slaughterhouse of structures with inscrutable Latin and Greek names. Lost in a new community of learners who all appeared to be doing just fine. Lost within myself as an empath, having to shove my feelings down my throat to participate in lab and lost when I didn’t know why my stomach was churning, unsettled.

And then after I had processed some of the experience by writing and reading (in particular, Meryl Levin’s Anatomy of Anatomy , Bill Hayes’ The Anatomist and Mary Roach’s Stiff); built a community I could talk to at school; and found more academic support, I became curious. The anatomy lab abounds with stories — the students dissecting donors and working with each other, the professors and teaching assistants directing the students, and the dead bodies on the table, about whom we know so little.

Over the next four weeks, I will share a series of essays with you in which I tell some of those stories. This writing results from the work of a summer, supported by a summer research fellowship in Medical Humanities & Bioethics at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, in which I interviewed nine first-year medical students, two third-year medical students, eight anatomy and medical humanities professors, two Anatomical Gift Program staff, three palliative care clinicians, two preregistered donors and one donor’s family member. Out of respect for their privacy, none of the people interviewed are named, and identifying characteristics have been removed.

I expect that many of you reading this are medical students, and so the anatomy lab is likely a familiar, although not necessarily comfortable, place for you. That being said, here are a few notes of clarification for any readers who are unfamiliar with anatomical donation: there are several ways to donate a body at the end of one’s life, but I am only writing about whole body donation for medical education.

People who donate their bodies to the Anatomical Gift Program at the University of Rochester will not be saving a 30-year-old who needs a kidney transplant nor contributing to the development of a new cancer treatment; they will be used as a teaching tool. Their whole body will be preserved and then used by students to learn anatomy or to practice surgical procedures. This is a topic of confusion that the Anatomical Gift Program often needs to explain to bereaved family members who mistakenly hope that their loved one’s suffering will directly transfer to progress on their specific medical condition. Anatomical donation is generally less stringent than other types of end of life donation, though disqualifying circumstances still include obesity, communicable disease or when an autopsy has been performed.

Anatomy lab is graphic, and as such sections of this writing narrate the process of embalming and dissecting cadavers. These essays are also pervaded by death and dying. I do not write with the intent to be gruesome but rather because the disassembled body has become the new normal for my classmates and me. These stories are traditionally held behind closed laboratory doors, but it is my hope to bring them into the light with both reverence and honesty.

I close with a linguistic note. The language in these pieces rotates through a laundry list of words to describe the people who donate their bodies to medical education: donor, individual, cadaver, body, person, father, patient, teacher, decedent, cremains, friend, protagonist, etc. I tried to mirror the language used by the interviewees, and therefore the word choice is relative to their relationship with the body. I speak for my classmates and from my own experience in saying that when you are elbow-deep in a dead body’s abdominal cavity, it is difficult to conceive of the person. We didn’t ever know them. This project is, in part, my attempt to know some donors as people. Next week, we’ll start out exploring the experience of medical students in anatomy lab, proceeded by anatomy faculty the subsequent week, and finally conclude with stories of donors at various points in their journeys.

Welcome to gross anatomy.

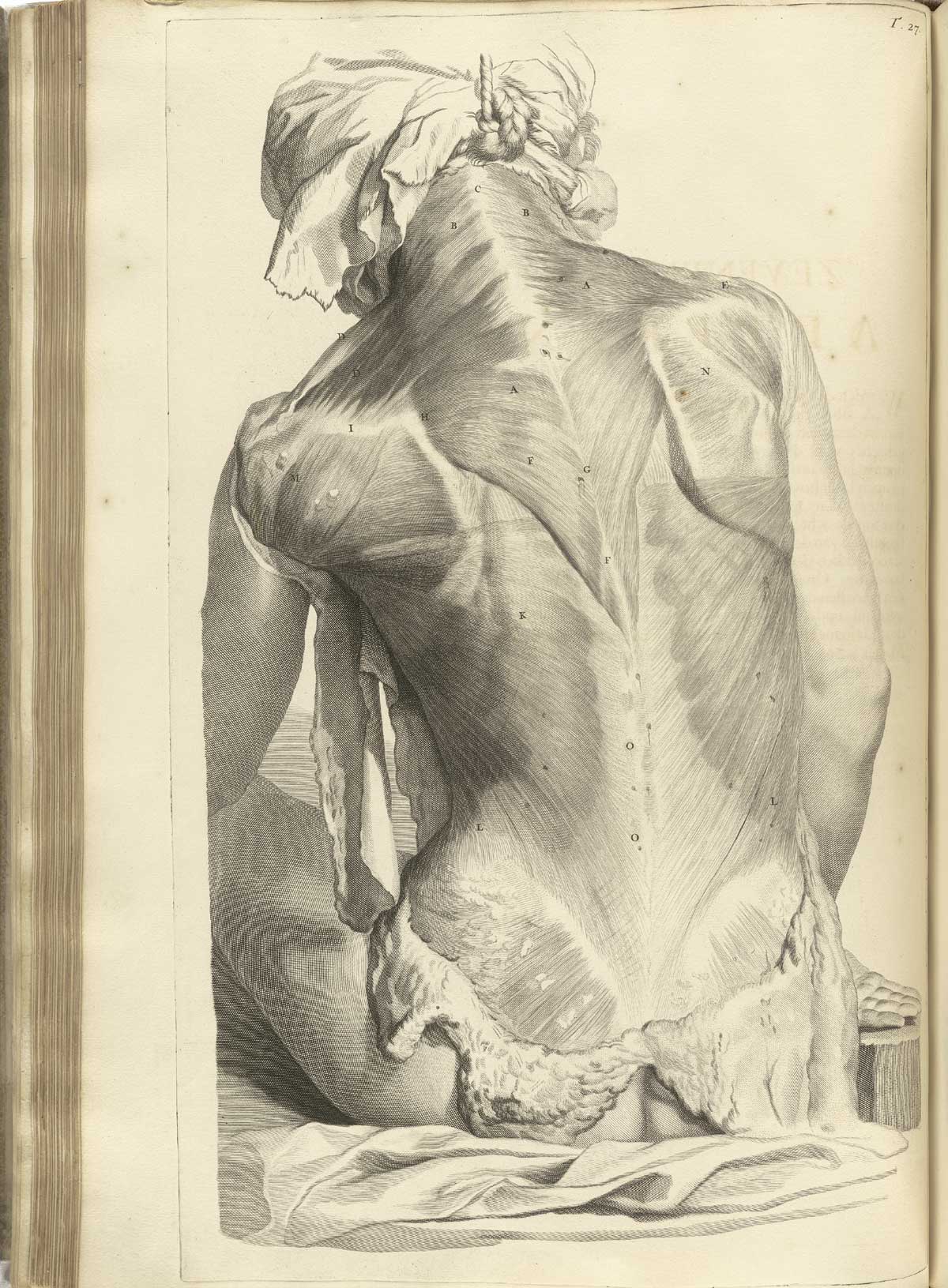

Image credit: Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine in the public domain.