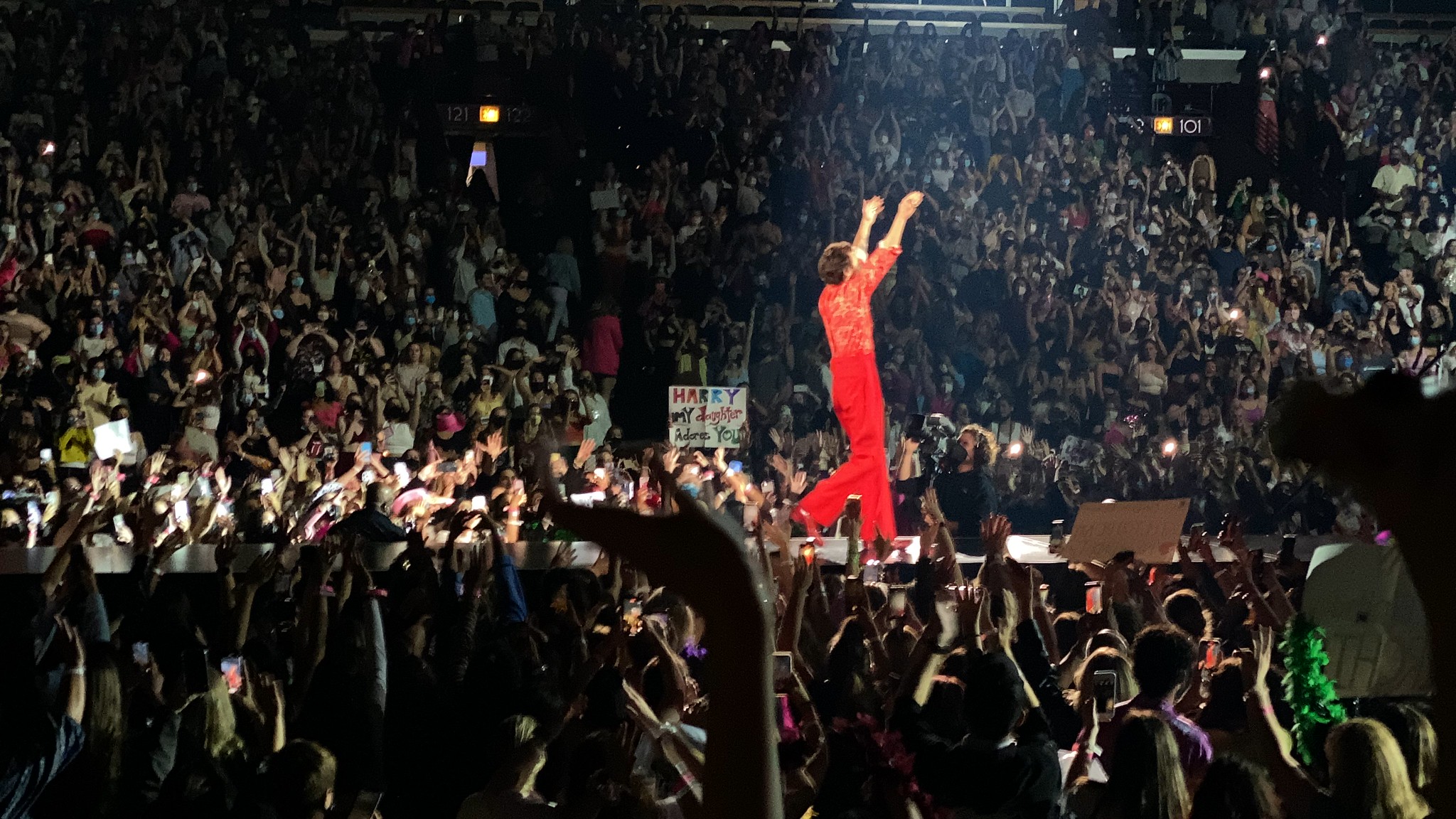

Harry Styles in the OR: Reflections of a Gen-Z Medical Student

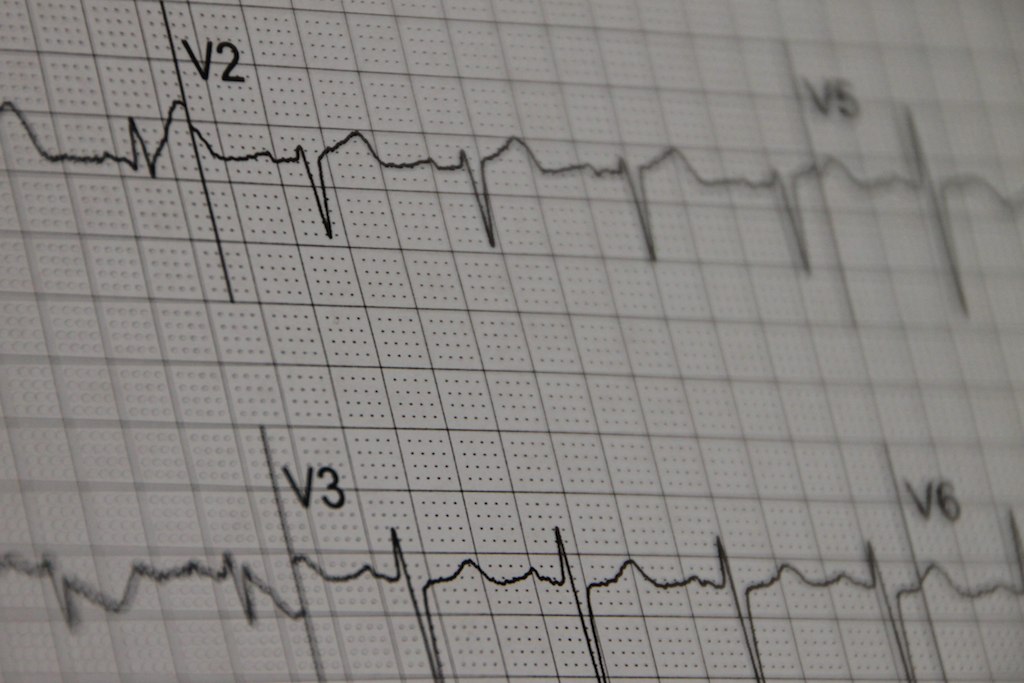

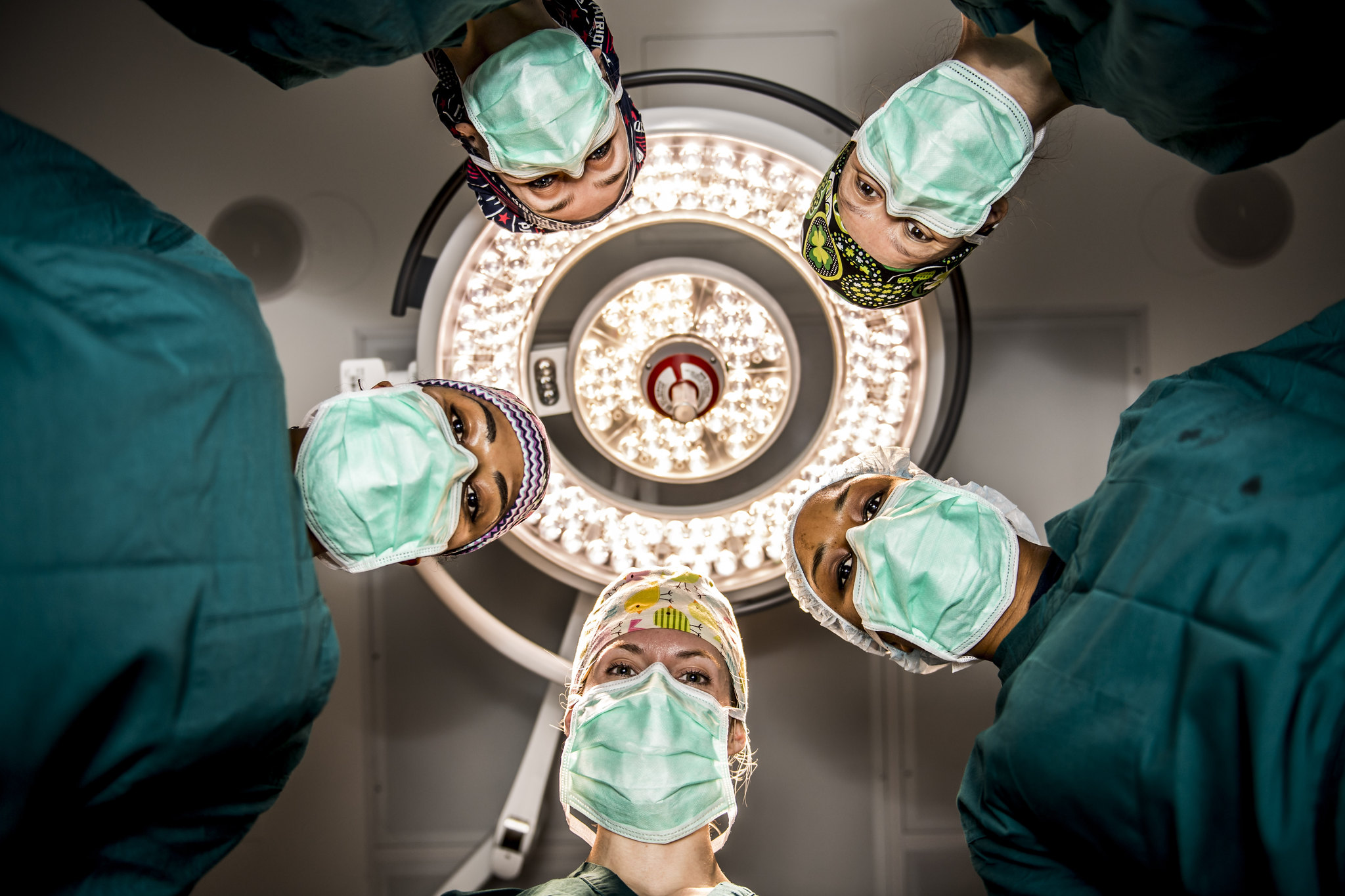

I had never truly scrubbed into an OR before, and I was incredibly terrified on my first day of general surgery. So I was skeptical when the scrub tech said, “Congratulations on getting here.” Yet somehow, against all odds, something clicked. Within the bright, sterile, cold OR, “Can’t get you off my mind,” rang out.