Yes, doctor.

I am running through the fluorescent-lit halls in my short white coat, pockets full of god knows what — surgical lubricant, suturing kits, saline flushes, pens and mystery stains from the day prior. Catching up to the group, I fall in line as we gather to begin rounds. I prepare to answer any question on the patient’s prognosis. Instead, my attending glares at me intently and asks for scissors. No amount of caffeine in my veins can erase my blank look as I stare back at the surgeon. I prepared for everything and still forgot the scissors. I scramble, sifting through my pockets for anything to help, but he has already written me off to discuss medications with a resident.

Two years of intense studying should have culminated in a feeling of strength. I ended my second year of medical school thinking I was now prepared to do anything. I was excited to be a problem-solver, armed with the mental acuity to recognize diseases from A to Z, ready to proceed with the next step in my clinical training. Now, in my third year, it is finally time to act like a real doctor. But our superiors treat us like their personal assistants.

Yes, doctor, I will run down these blood samples while you finish the procedure.

Yes, I’d be happy to bother the radiologist a third time to read the scan immediately.

Yes, I can definitely grab some coffee for you.

We listen carefully and execute tasks precisely, yet this still feels wrong. Why is it that all we can do is be “yes men” to senior doctors? Why aren’t we treated like the professionals we are training so diligently to become?

As we exit the room of our last postoperative patient, a shared sense of comfort settles among the students. We survived the chopping block, but now the next phase begins. As the rounding team disassembles, we rush to review the charts of our assigned cases. As if sprinting in a race, we pore over every minute detail, every comorbidity, every previous note we can read in five minutes. With an air of confidence, I head off to introduce myself to my next patient in the preoperative holding area.

Everything is in order as the attending and resident walk in to speak with the patient. The stern surgeon reviews the upcoming surgery with the patient: a simple laparoscopic removal of fibroids in the woman’s uterus. Trailing behind quietly, I mentally go over the possible questions I could be asked during the procedure. Just as I get lost in my thoughts, I bump into the surgeon.

He turns around and asks me point blank, “Can you do me a favor? The patient doesn’t have any family members picking her up after the surgery. I will pay for your Uber to drop her off home and return to the hospital.” I blink, perplexed and thrown off by such an unusual request. I look at my resident for guidance, but she purposely avoids eye contact.

“Yes, doctor,” I smile, “Just give me her address and the time I should take her home.”

Determined to make an impression, I have become the “yes man” I so despise. My attending’s eyes light up as he promises to reward me upon my return. My resident knows all too well the position I am in but leaves for the OR without a word.

My worries over the liability of taking a patient home, the risk of going off on my own, and the surgeon’s disappointment in my abilities grow throughout the day. Uncomfortable with this task, I weigh the potential consequences of my options. As I vent to my classmates over lunch, the chief resident pulls me aside. She reassures me that a decision to deny my attending’s request will not reflect poorly on my evaluation. She will speak with the attending to find alternative means for the patient to get home safely.

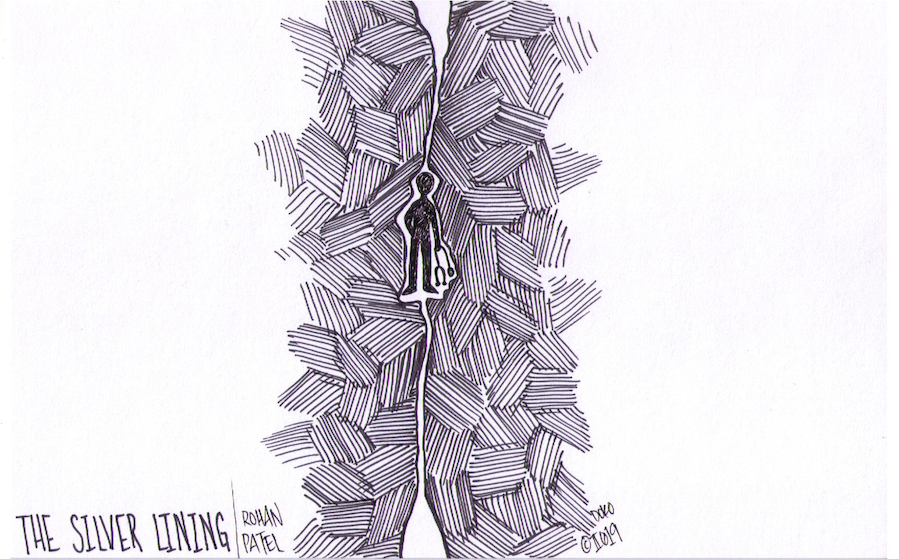

Relief starts to settle over me, but the unnerving feeling that I had crossed an unforgiving boundary lingers longer than expected. Like rungs on a ladder, the hierarchy of the medical profession places experienced physicians at the top and medical students at the very bottom. How can we speak out when our seniors loom so high overhead? From the beginning, we are taught to be “team players” with the underlying expectation that we should always be ready to assist no matter the circumstances. But it does not take long for us to realize that when we do not meet our superior’s expectations, no matter how unrealistic, we are deemed unworthy of our superior’s energy or attention.

Are our voices so small that we need to keep quiet, even when it goes against our morals? Have we abandoned our goal of becoming physicians only to become our seniors’ assistants? Are we ungrateful for not wanting to listen to the teachers who are training us to be better physicians? Is our worth defined by one small mistake? Are we only deserving of one chance?

No, doctor.

As I continue to mull over the daunting repercussions of defying my attending, the chief resident winks at me as she heads to the OR in my stead. “Rohan, enjoy your day,” she says. She smiles and fearlessly walks off, giving me confidence that everything will be alright. Like my guardian angel, my resident had come to my aid, showing me that I don’t have to fight this battle alone.

That day, I learned a valuable lesson. When we as medical students graduate into the long white coat, we must realize that we will inevitably be impacting the next generation of doctors. Mistreatment and disrespect should not be a culture that we perpetuate or that our juniors become accustomed to. The practice of collaboration can easily overpower the hierarchical negativity that some doctors spread. Like the chief resident who defended my position to the stern attending, we must reclaim the phrase yes, doctor. By validating our struggles while advocating for our juniors, we can set the tone that respect is the new norm. After all, we must encourage growth and empower our colleagues to be their best selves. We must realize the gravity of our roles and treat peers and colleagues with respect. Within a new culture that fosters empowerment, it will be easy for us to come together and proudly say: yes, doctor.

From the outside, medicine is a grand profession — physicians and trainees work together to help those that are in need while saving lives. However, every day we are faced with darkness that does not get shown to outsiders. How we deal with these obstacles truly shapes our experiences within this profession, often leading to physician burnout. This column will focus on some of Rohan’s personal experiences facing the dark sides of medicine, while shedding light on how one can overcome these challenges. After all, there is always a silver lining through the darkness.