Unprecedented. No word has been used more often to describe this remarkable year. At some point in the distant future, medical students of this era will recall being summarily removed from clinical rotations, uncertain if we would be asked to stay home or serve on the front lines of the fight against a global pandemic.

We will recall when, during the summer of 2020, the moral and political duty to engage with the most momentous anti-racist movement since the 1960s reanimated a nation paralyzed by fear. By the fall, cataclysmic wildfires on the West Coast poisoned the air from San Francisco to New York City. Coronavirus, cultural upheaval and manifestations of climate change all bore down on us as we entered the most consequential and divisive national election in living memory.

As medical students we’re taught to keep our personal politics out of the clinic. And yet, the nation’s politics seep into nearly every aspect of medicine. The structural determinants of health that make our patients sicker and harder to treat are consequences of political decision-making; radical expression of political concepts like freedom and self-determination have dramatically worsened America’s experience of COVID-19. Insofar as politics fundamentally shape how medicine is practiced, our responsibility to patients requires that we develop and maintain an expansive political consciousness.

With political consciousness-building in mind, the remainder of this essay will review the history of another period in American history defined by a simultaneous struggle against government oppression and communicable disease: The American Revolution. Our review will expose the origins of American interpretations of freedom and self-determination. We’ll end with a discussion on why political systems defined by a single, narrow conception of freedom are ill-suited to combat many modern public health threats, and what we as medical students can do about it.

Before we begin our analysis, it’s important to acknowledge that the lofty appeals to freedom that defined the American Revolution are invariably complicated by the period’s malignant racism, sexism, systematic oppression. The War of Independence was never meant to secure the Enlightenment principles of freedom and equality for anyone but white men. Keeping the period’s intellectual contradictions and limitations in mind will help distinguish the period’s problems and solutions from our own. With that caveat in place, let’s turn to the events that laid the foundations for the political troubles we face today.

By 1775, many American colonists were fed up. The American colonists understood themselves to be British citizens, entitled to the full rights and freedoms afforded them by law and custom. King George III and his government seemed to disagree when they failed to explicitly extend protections enjoyed by British citizens in Britain. To them, it appeared the colonies were unique entities, which entitled the Crown to keep a standing army stationed in cities up and down the Atlantic Coast during peacetime, even if the English Bill of Rights of 1689 expressly forbade such an action. Besides, the young colonies had proven unruly; a standing police force might help keep things in order.

Police states are touchy. A slight bump here or an accidental nudge there can send matters spiraling out of hand. Such volatility helps explain why in 1770 a simple disagreement near the Boston Custom House quickly escalated into a violent confrontation between British soldiers and the townspeople, leaving five Bostonians dead. The sentiments soured by the Boston Massacre would be further spoiled by the Coercive Acts, a series of laws that both robbed Massachusetts of its right to self-governance and kept British officials from having to stand trial in colonial courts.

Every British transgression, no matter how small, served to remind the colonists that they were not, in fact, protected by the rule of law as they were led to believe. To make matters exceedingly worse, colonists were being taxed for the privilege of living under imperial rule.

While many colonists held out hope for a peaceful resolution of grievances with King George III, Patrick Henry, a leader in the powerful state of Virginia, had enough. He made his sentiments known to delegates of the Second Virginia Convention late in 1775, offering a simple solution to the colonies’ woes: raise a force of Virginians to ensure Virginia’s defense. Such a force would eliminate the justification for His Majesty’s soldiers and the high taxes their presence demanded. Henry’s provocation sent the convention into a heated debate about whether such an action would invite war with the British. In defense of his resolutions, Henry delivered his now-famous speech with an ultimatum that grabbed the delegates by their spiritual collars and refused to let go: Give me liberty or give me death! A month later, a milestone in the fight to reform government, according to Enlightenment ideals, began in two villages north of Boston.

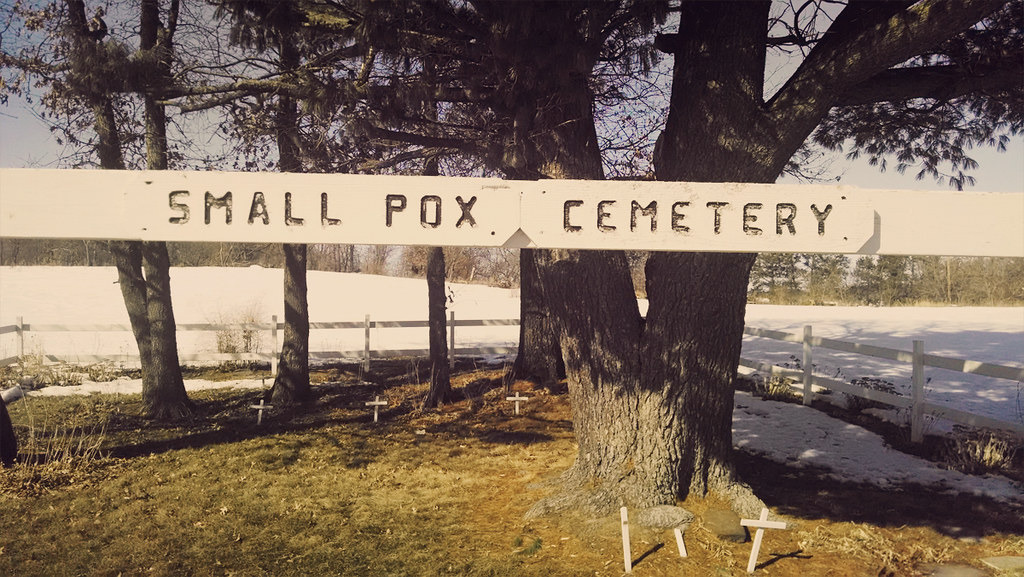

Just as the colonists took up arms to tear down the police state in which they lived, North Americans of all backgrounds began facing down a second, even deadlier enemy to freedom: smallpox. The variola virus, present in the Americas since Columbus’s arrival in 1492, had chosen this particularly fraught moment to resurface in the British colonies of North America.

With no known treatments and an understanding that close contact with the infected increased the chance of falling ill, colonists implemented quarantine and self-isolation programs. Some opted for inoculation (also known as variolation), a forerunner to vaccination that required inserting pus from a smallpox patient into an incision made in the healthy recipient’s arm. Variolation caused disease in the recipient, in some cases even leading to death. Despite these dangers, the prospect of immunity was enough to convince Abigail Adams to inoculate herself and her family. George Washington reached the same conclusion for his troops after watching, helplessly, as the disease ravaged soldiers on both sides.

Today, Americans once again find themselves beset by the challenges of 1775. We are pushing back against the dual threats of police brutality and a deadly communicable disease in the midst of deep political division. Like a people besieged on all sides, attention to one threat raises the possibility of a sneak attack by the other. Our shouts of protest against police violence and systemic racism are muffled by the masks protecting our faces, lest we inadvertently invite the coronavirus into our lungs, then families, then communities. Despite a raging epidemic, Americans of 2020, like the colonists of 1775, have been left with little choice but to risk illness and violent ends in order to secure the full rights and freedoms afforded to us by law.

We are still years away from being able to fully reckon with the lessons of this year. Certainly, the events of 2020 have reinvigorated civic involvement. They’ve also reminded us that democratic politics and medicine take as their goal the same basic ideal: the enhancement of human freedom.

The overbearing nature of our current challenges might lead us to believe that our freedom depends on ridding ourselves of forces that restrict our freedom (i.e. structural and implicit racism, police violence, gross income inequality, climate change, coronavirus). This is what philosophers call negative freedom. Those who advocate for small government do so for the same reason as those who advocate for police reform: fear that an over-empowered state is a threat to human freedom (and sometimes, to life itself).

While history is rife with justifications for building political systems to protect negative freedom, the costs of decentralized power become evident when a nation is met by challenges as harrowing as war or pandemic. Like an invading army, a communicable disease cannot be defeated by the uncoordinated, undisciplined effort of even a powerful nation, at least not without incurring incredible losses (Soviet losses during the Nazi invasion of Russia serve as a poignant reminder of the costs of being unprepared for a powerful enemy).

In order to push back against an adversary as powerful as coronavirus, the best of American ingenuity and will-power must be organized and overseen by a government able and empowered to lead. Yes, by empowering government in times of crisis we invite the possibility of future tyranny, but what sense does it make to invite significant, perhaps fatal, injury now to avoid the risk of possible injury later? True existential challenges in the present not only warrant but demand such risks be taken.

National emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic help us see the shortcomings of building a political system too focused on limiting government power to protect negative freedoms. A significant portion of the nation is currently so suspicious of federal overreach that they would rather risk exposure to a deadly pathogen than invite the vague possibility of tyranny and oppression down the road. However, if we don’t give the government the power it needs to effectively organize the fight against COVID-19, we threaten not only the lives of fellow citizens, but also the political economy on which we all rely.

Can we escape this dilemma with our health and freedom intact? Yes, but only if we acknowledge the reality that certain problems cannot be solved by individuals and decentralized governments. As medical professionals who regularly deal with death and disease, we are well-positioned to advocate for balancing negative freedom with positive freedom, which means providing individuals the power and resources needed to manifest their will. How do medical students start down the road to becoming effective advocates for positive freedom? First, and most importantly, by recognizing our position. As the incoming workforce for a profession desperately short on staff, our will, if expressed collectively, can reshape medicine into a force for the advancement of positive freedom.

Second, students must organize and work locally. Get involved in your local chapter of White Coats for Blacks Lives, or find a community organization working with individuals experiencing homelessness or food insecurity. However you choose to develop your political consciousness as a medical student, be sure the experience requires you to intertwine some amount of your own well-being with the well-being of those suffering from the shortcomings of our political system. Consciousness grows when we have an emotional stake in the matter at hand.

Let’s hope for our own sake, and for our patients’ sake, that the sacrifices of this year inch us closer to an America courageous enough to admit that a political system obsessed with negative freedom can itself be an enemy of freedom.

Image credit: Small Pox Cemetery (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) by Kayla Nicole