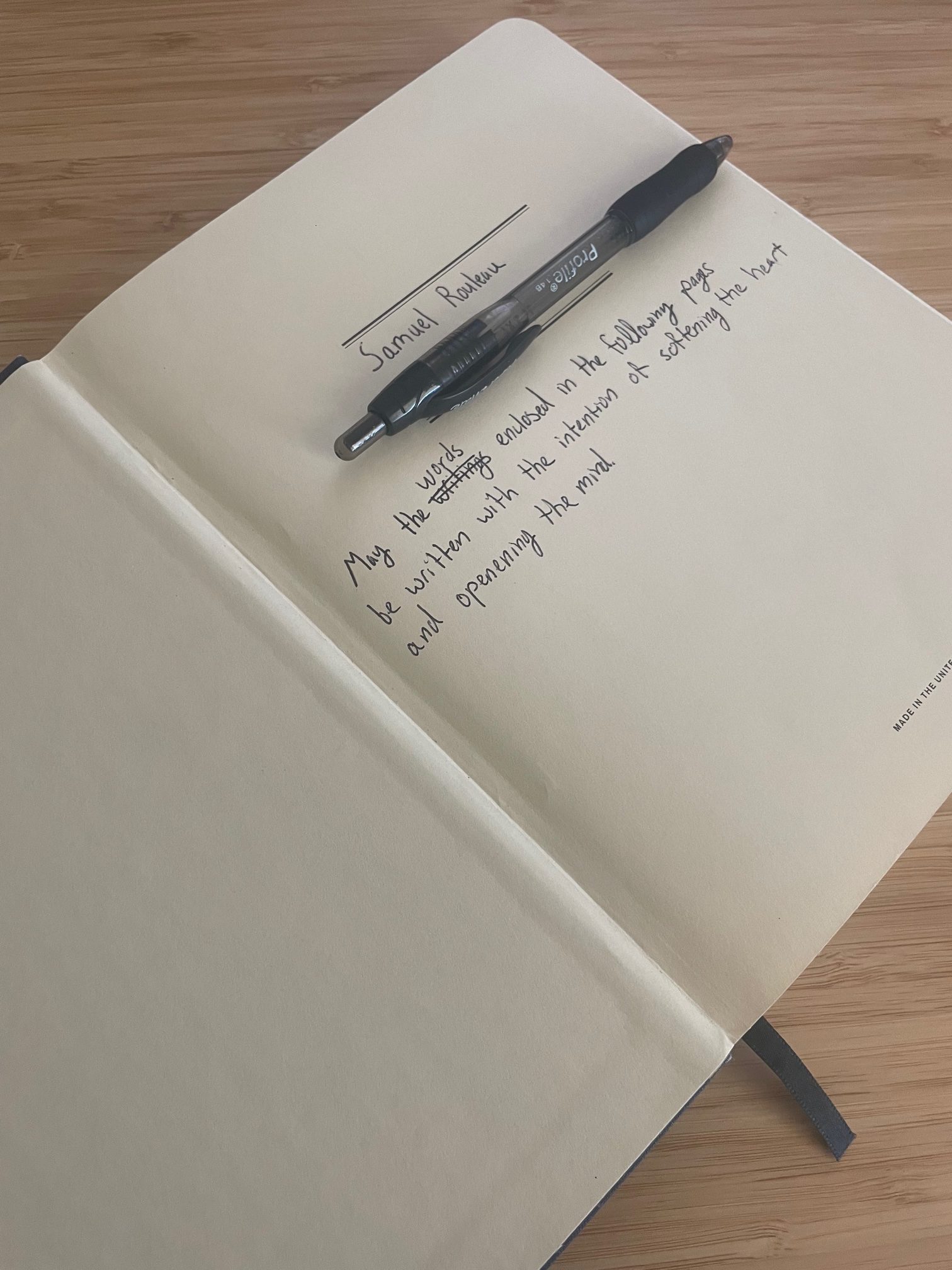

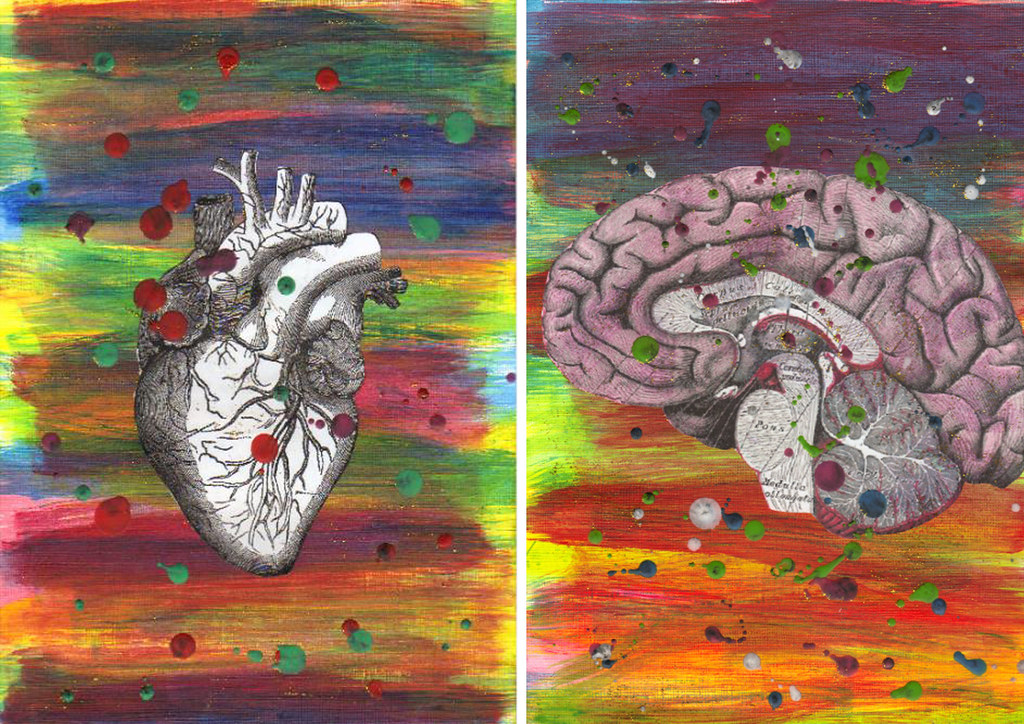

Story(ies) of Myself

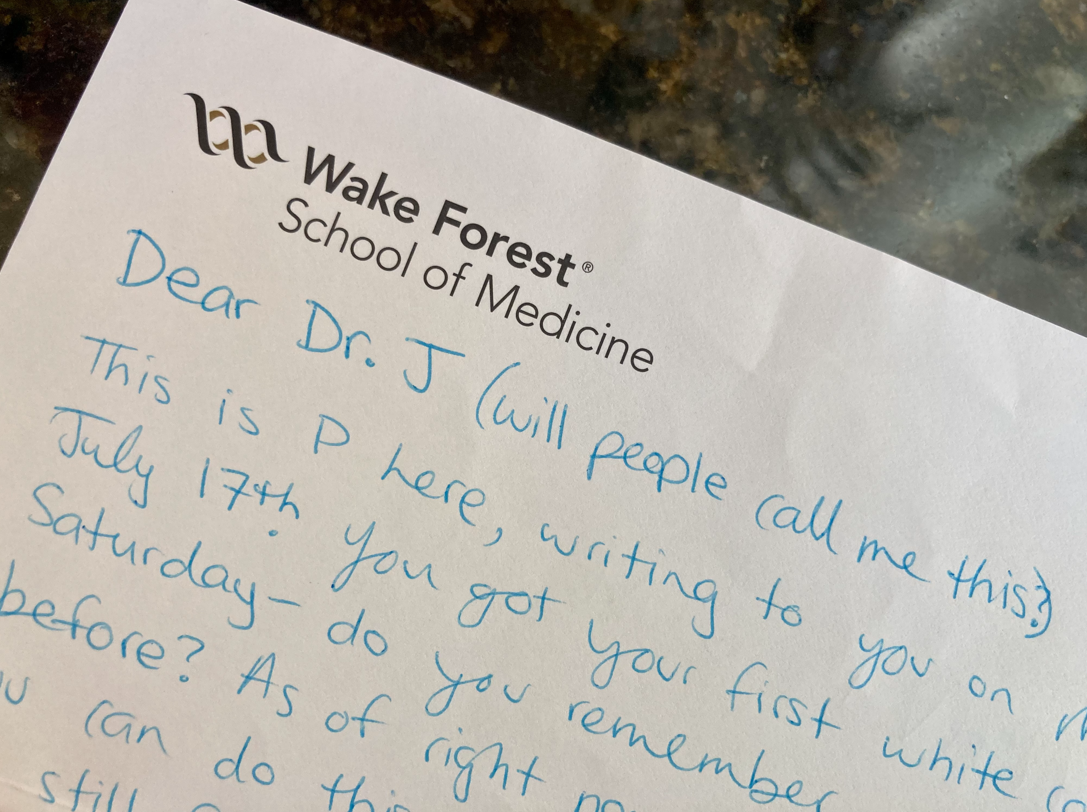

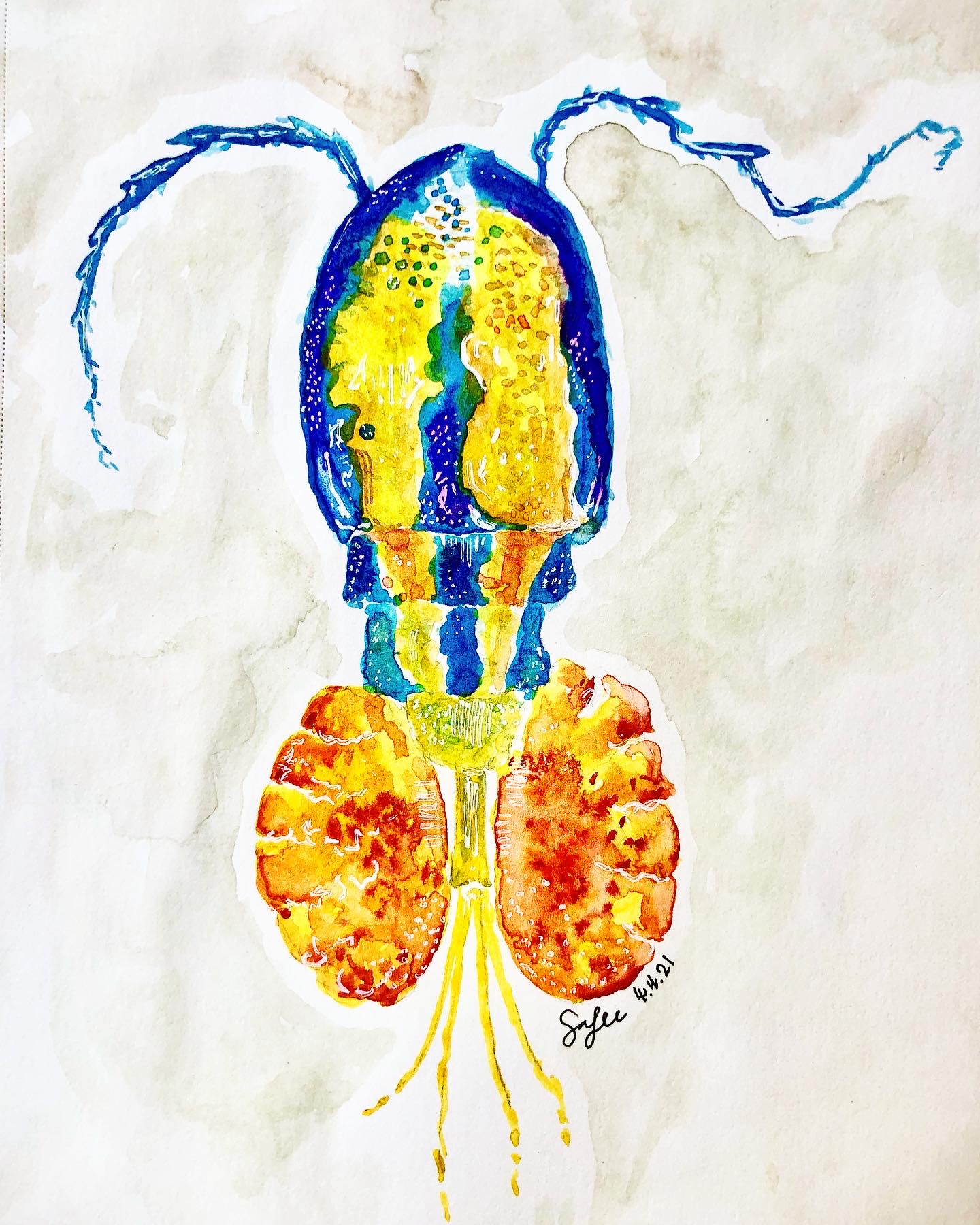

The power and beauty of writing rest in a process of active narrative formation. The act of expression helps us make sense of what happened, integrate this into our sense of self, and clarify our values that will influence our next steps. Conveniently, our expression serves as a record of both identity and narrative formation, giving us a glimpse of ourselves more intimately than we typically take time for.