Editor’s note: We are featuring a series of essays by Kate Crofton on anatomy lab. Her essays are based on 27 interviews with medical students, faculty, clinicians and donors.

This is the third installment in the series. Read the fourth part of the series here. Read the second installment here.

It is the day before the first anatomy lab for the first-year medical students, and a single professor walks alone, up and down rows of tables laden with 26 naked, embalmed bodies. He silently shares a few minutes with the donors, a private thank-you. Soon the donors will be covered in white sheets, and the students will tentatively spill through the locked wooden doors of the labs, a rush of anticipation, teamwork, questions and learning. But right now, no one makes a sound. There is no buzzing of saws, whirring of the suction machine, or gentle clinking of hemostats and Metzenbaum scissors against the metal tables, no nervous laughter, exclamations of discovery or confused mumblings.

The professor will be joined by an eclectic team of his colleagues. They are educators who use dead people as their teaching medium. They spend hours on end in rooms reeking of formaldehyde. Above all, they care deeply about doing their work with respect. With their turquoise gloves, blue paper surgical shoe covers, rainbow of expo markers, memorized atlas page numbers, thoracic spine necklaces, golden dissecting scissors and pockets full of little colored wires, they will help each student learn to find their way.

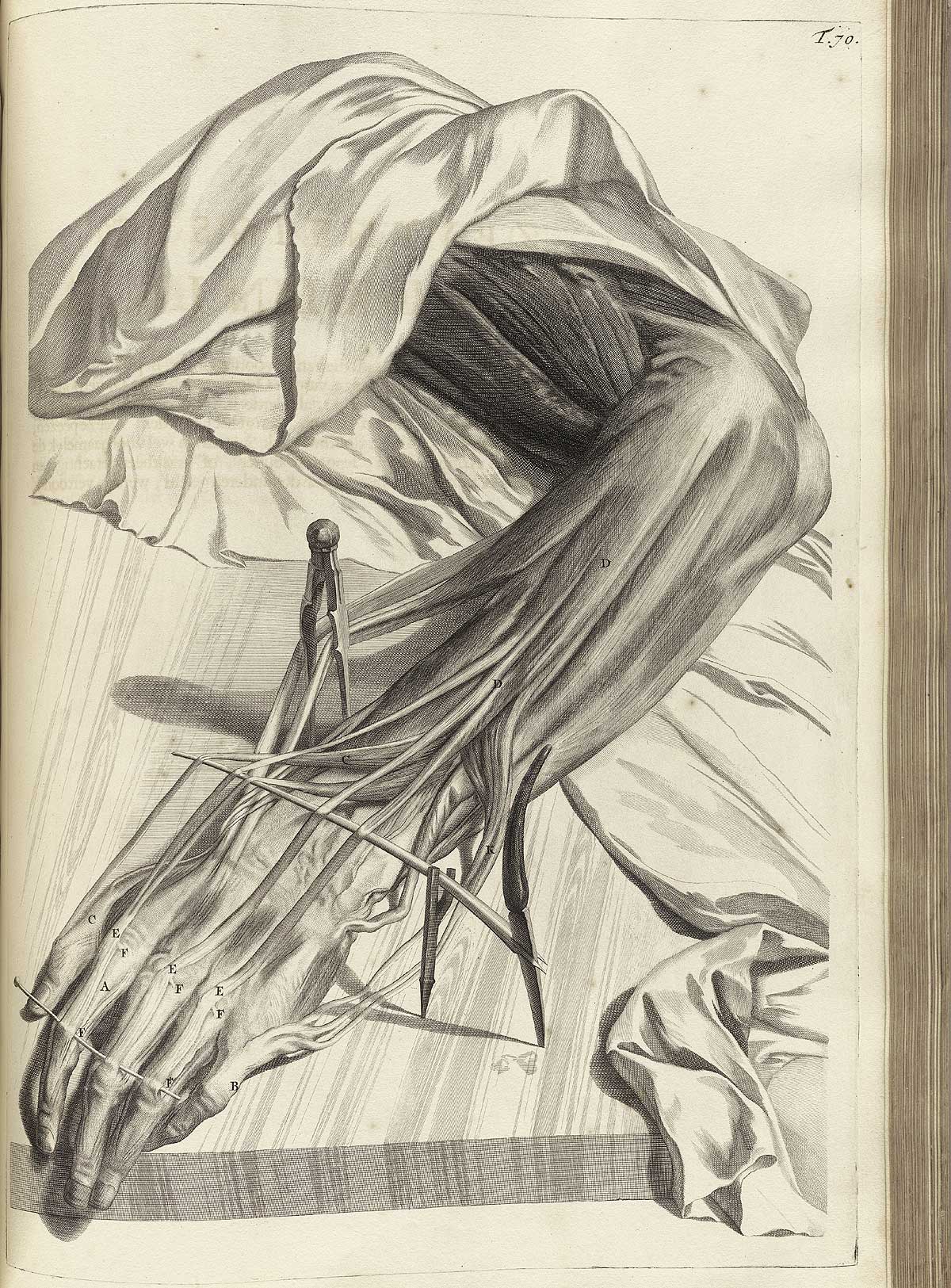

These professors find beauty in anatomy: the relationships of the structures to each other, the functionality of the human body, unique variations and even pathology. The brachial plexus dissection is a favorite of one professor, a lab which reveals a complicated bundle of nerves branching and recombining to serve the arm. For another, the most beautiful structures are the hands and the head, the parts worn outside of clothing that “express personality and individuality.” They love the search for structures: “When you first look at the tissue, it looks like a mess — non-descript gauze. There is no real reason to think there are nerves or vessels running through that. But then once you find them and then you see how tightly packed things are, you realize just how incredible it is.”

Another instructor asserts that her upbringing in a family of hunters contributed to her early interest in anatomy and her understanding of the place of death in the lifecycle. “My brothers and my dad hunted, and so from the time that I was really little, I was used to seeing deer butchered in our garage. I was struck by the intricacy and the beauty of how a body could be put together and function properly … I can remember my mom buying one pound of ground beef, and she would make our meals for the week — goulash, Spanish rice, things that would spread it out. I realized that deer put meat on our table and kept deer from starving; it managed the population. Death is a natural part of life.”

My dad and brother are also deer hunters, and I remember deer carcasses hanging in my dad’s shop during my childhood. I perched on overturned five-gallon buckets amidst sawdust and pine two-by-fours and watched as my dad sliced away the hide and wrapped chunks of bloody meat in crisp white freezer paper. I loved the warm, buttery taste of venison and intuited more easily then the cycling of life into death into life again. The deer were beautiful, running through our hay fields, and they were beautiful still as carved up slabs of meat in the deep freezer.

To find beauty in the anatomy lab might seem crass; after all the mechanical process of disassembling the donor is brutal, and at the end the body is a carcass, a dried-out pile of flayed skin and bones. Professors acknowledge this difficulty, “I am always intrigued by different things that I see in the lab — beautiful dissections — and I know the word beautiful is sometimes a complicated word in that space … You’re right, it’s by seeing many donors over time that you come to appreciate that we’re all the same, there’s a pattern, but we’re also all unique. Everybody has an interesting story, and their body often tells that.”

I interrogate the professors for a list of the most fascinating anatomy they’ve seen. They oblige with developmental abnormalities: situs inversus, horse-shoe kidneys, bifid muscles, extra blood vessels and abnormal arrangements of nerves. They also mention impressive pathology: swollen cirrhotic livers, big black lymphatic balls of cancer, white hardened atherosclerotic plaque, occluded coronary vessels and cerebral hemorrhages. They recount biomedical devices and remnants of medical procedures, too, a demonstration of medicine’s advances to thwart pathology: coronary bypasses and stents, pacemakers, orthopedic prosthetics and deep-brain-stimulating electrodes.

I ask one professor if there’s any anatomical anomaly that he’s still hoping to see in his career. He gently chides, “No, it’s not like I’m going to go out looking for donors to have things that I’m interested in; that’s not the point.” And I realize that I have indeed missed the point. The anatomists don’t see donors as collections of interesting or rare anatomy but instead see them as their partners in teaching us.

The anatomy instructors are guardians. One professor explains that she feels a deep sense of responsibility to take care of the donors so that they may teach her students, “It’s funny, I’ve described myself as the curator of those donors. I feel like I’m a caretaker of sorts. When I walk into that anatomy lab, I find it to be a very comforting space. When I go in there it’s quiet and I think about the various lives that are represented by the donors in there, and I think about that gift that they were willing to share to let all of you learn.”

I picture an art gallery, with paintings carefully framed on the walls. The anatomy instructor appears, robed in a long white coat and blue scrubs, hair held in place precisely with a barrette. She softly dusts each painting, adjusts the lighting, and adds a placard underneath each one so that it may be better understood. “My job is to make sure that all of them are cared for well and that they are the best learning tool for all of you to learn that anatomy and have it be memorable.”

The relationship between professor and donor can prompt reflection and even conflict, in the professor. When a young medical professional died of a drug overdose and donated his body to medical education, it provoked one lab instructor to be more reflective than usual. “An 87-year-old died of a heart attack — I’ve heard that one before, but a 27-year-old … is there something that’s fundamentally been lost even more in the 27-year-old? For whatever reason I did stop and think more and feel a little bit sad, not to the point of tears, but sad and reflective.”

She pauses, and then continues, “I also felt grateful and then felt a little sick about feeling grateful because that dissection was really beautiful. It looked so much like [the anatomy textbook] a lot of the time — the muscle integrity, color, shading, shape and distinction. Things weren’t blending together, there was no marbling of fat infiltrating the muscles. It was such a beautiful, easy dissection and the students learned so much.”

These professors didn’t always have such mature relationships with the donors. One faculty member recalls her first experience in an anatomy lab as a student, looking at the donor and thinking, “I don’t know if I recognize you as a person or a dissection tool.” I relate deeply to her memory, and it resonates also with many of my interviews with students. As novices in anatomy, it’s much more difficult and requires a more deliberate effort to switch between viewing the cadaver as a body and as a person. I am cutting the body, and the person is gone, but the person chose for the body to be here. It’s clunky. The professors are more fluid with this duality and coexist with it in a more peaceful way.

When I ask the same professor whether she now views the donor as a person or a body she responds with an analogy: “It’s like electrons in orbitals. They can be in one place but never in-between. I try to maintain respect for what I imagine as the person that they were in the decision that they made to be here, the life that they had. But at the same time, I don’t believe they’re alive anymore or have any sort of soul inhabiting what’s left. There’s all this meat and bones left behind, but there’s nothing that can be hurt or embarrassed.” The donors are gifts, teaching tools, partners and even friends, extending an invitation to come learn.

The anatomy lab is not an immediately comfortable place for everyone, and even the professors, whom we view as our seasoned guides, once needed to habituate to the space. An instructor recalls her first time leading an anatomy course, “I had a really profound visceral response to every dissection. For the first half hour walking in there, I felt nauseated, I felt faint. I always made sure I was bracing myself on a table or against a wall just in case, and I didn’t admit it to anyone because I was in charge.” I recollect my own experience in lab, repeating a silent mantra “mind over matter” as the room clouded over and the din grew distant, willing myself to remain vertical. “Mind over matter” carried me through the course for weeks, and I left the lab each day feeling like a soggy balloon, sapped of all emotional reserves.

The professor continues, “I’ve been trying to figure out what changed. My first time [as a student] I was fine, and this time I’m falling apart and not admitting it to anyone. I think a couple things — the crazy amount of stress of trying to learn anatomy, run the course and teach all at the same time. Also, in that instructor role, you can’t immerse yourself in dissection. You’re walking from one table to another and watching as people make these incisions and take things apart, and you don’t have control over it yourself.”

She describes being in lab one day when students were dissecting the lower extremity. At that point, the legs had been severed from the trunk of the body, and they were propped at ninety-degree angles to practice the anterior drawer test. A living person might assume the same position, perhaps strewn out on the sofa reading a book, feet on the cushions and knees bent in the air. It didn’t feel right, “because it [aligned] too much with what I think an intact human looks like.” She adapted and the second year developed strategies to be more comfortable as an instructor in the space. “I knew that if I could reduce the smell, that helps. I got Vicks Vapor Rub, and I would wear a mask that year. I realized that getting hands-on as soon as possible helped, so I made sure to get in on someone’s dissection as soon as I got in the room. Partly just seeing it again and again, I habituated.”

To our instructors, the donors are far more than dead bodies; they are teachers. Textbooks and plastic models only represent our notion of “typical,” but donors show us great variation. In an even voice with steady conviction, an anatomy instructor explains, “I see [the donors] silently saying ‘Bring the book over here, and if you don’t see it, change the book because this is real.’ The anatomical donor population provides an immediate education of what we currently understand about how human bodies function — and some of the ways they stop functioning.” The donors inform our knowledge and make us better scientists and clinicians.

They also move us to be better people. Groups in power have historically used pseudoscientific arguments to justify their social status. For example, in the 1800s Samuel George Morton thought that it was possible to define the intellectual ability of a race by skull size. Rigorous scientific methods and access to good data have refuted his racist claims. If our anatomy is all the same, then how can biology determine the inherent superiority of one class of people? As one professor believes, the donors show us the importance of inclusion and respect for all human beings. “There used to be quite a bit of wrong speculation of how bodies were put together and how they functioned. Over the past century, we finally have moved into an understanding of how things really work, and the donor population is a large part of the reason why we now understand.”

The donors help us understand anatomy, and they also help us come to terms with our own mortality. I ask one professor if anatomy has changed his view of death. He tells me no, rather it’s the opposite; because of donors, his personal grief has emerged in the classroom. The year that his father died, the first day of class fell on his father’s birthday and there happened to be a cadaver in lab that resembled the professor’s father. A first-year student in that class had recently lost his mother to breast cancer. When the student peeled back the white sheets in preparation for anterior dissections, he discovered a breast-less chest bearing the scars of a mastectomy, “and so we both had these acute reminders of the grief that we were going through.” When the same professor’s wife of thirty-eight years died of colon cancer, he knew that he would need to take extra care in order to be able to teach the gastrointestinal anatomy. “Well it’s not like all 26 cadavers died of colon cancer. So it wasn’t something every day that I had to deal with. The stress for me is the teaching part; I want to make sure that I’m doing a good job … You put things aside, and you can’t be thinking about grief and the death of someone all the time, you just wouldn’t be functional. It’s not that I intentionally put it aside, it’s just other things become more important in the moment … and then I go home and think about it.”

Anatomy instruction has both accelerated and become more humanistic over the last fifty years. A professor contemplates his first anatomy course as a student in the 1970s, “I can remember that there were students who put clothes on their cadavers. Surprisingly there was not a lot of student reaction to that; people just weren’t as thoughtful or as sensitive about it as they are now. We didn’t do it, but someone did it to our cadaver. That’s probably my most vivid memory.” Decades later, he shifts uneasily in his chair and his eyes moisten. Some of our professors’ rules make more sense now. Photography is not allowed in the gross anatomy labs, only medical students may enter the locked space, and we are warned to treat the donors with respect for their personhood.

He continues reminiscing, “Although [medical school] had a body donation program, we also had unclaimed bodies. Our cadaver was African-American, and I’m going to guess that he was unclaimed … just from the wear and tear. So that’s changed now too, the anatomical program has changed. Anatomical gift programs really began to get formalized in the mid-20th century and weren’t really codified well until the 1960s.” All the cadavers used at our medical school today are donated. I try to imagine what it would feel like to dissect a body that was discarded at the hospital or county morgue, perhaps because the decedent’s family couldn’t afford to pay a bill. It feels ugly. I am grateful for my donor’s gift of his body, and also immensely grateful that it was a gift. The professor agrees that he is “much more comfortable” with our exclusively donor-based anatomy program.

A student’s time in anatomy lab today is abbreviated compared to our professors’ educations. “[My medical anatomy class] had 300 hours. When I first came here in 1985, we had a 190 hour [anatomy] course and 160 [of those hours] were laboratory. We are down now to less than 100 hours of lab. Surprisingly the detail [that we teach you] hasn’t changed that much. We had to become more efficient.” Our education today prioritizes early clinical exposure and multi-disciplinary learning. A consequence though, is that it is more difficult for the anatomy professors to get to know their students, and there’s less time for students to process the experience as they rush to learn all the material.

What do our anatomy instructors want us to learn? “Hopefully some basic anatomy,” replies a professor, “but I know that unless you are using it, it’s going to disappear. So, I’m sure that if I started asking you questions …” I laugh nervously, and stammer, “please don’t” desperately trying to remember the branching of the cranial nerves in case he does quiz me. Maybe he has a skeleton in his office that he will pick up, pointing to the pinprick fossa of the skull? But he continues, “More importantly is when you get to the clerkships during your third and fourth years and someone’s going to ask you some anatomy … do you know where to go to review that? Have we made you a good learner?”

Other professors respond, “We need to have excellent physicians, and to be an excellent physician you have to know anatomy. The best way to teach anatomy is through dissection.”

“Equally important, you’ve learned about yourselves.”

“You have to learn teamwork, patience, perseverance, humility and gratitude.”

It’s these moments: watching lightbulbs go off for students as they make a connection across disciplines or overcome challenges, that come up again and again as our teachers’ biggest joys. “I’ve always been motivated to teach, and that stems from when I was a little kid taking swimming lessons. By the time that I graduated from tadpole to polliwog, I would help as a teacher’s aide for the group behind me. I loved when people were able to gain a skill, and I found being part of that process to be very rewarding. I always felt somehow that teaching needed to be part of what I would do for a living.” Teaching forms a key part of their identities.

And so, I am surprised, though maybe I shouldn’t be, that when I ask if they want to be anatomical donors when they die, a high proportion of our professors responds with an emphatic yes. (One says that if he’s healthy enough, he’d prefer to be an organ donor. Others qualify that they’d personally be interested in whole body donation but would need to take their family’s needs into account, and some haven’t yet settled on their end of life wishes.) These are people who know with staggering detail everything that happens in the anatomy lab. They know the entire series of maneuvers of the gloved fingers, scalpels, scissors, chisels, and saws required to deconstruct and study what may someday be their cold, bloodless bodies on the dissecting tables.

“It’s because I know exactly what happens in that space that it’s important to me. I realize how thorough the dissections are, I realize how much students can learn, I realize how memorable those experiences are, and I realize that it is a space for learning more than just anatomy. If I can support that for one more year, that’s incredibly important to me.”

I imagine that I am again a first-year student several weeks into gross anatomy lab, and the funeral director visits my table to tell us about our donor. How startling it would be to learn that the body that we had been dissecting belonged to an anatomy professor. One instructor tells me that she loves the ideal of the reveal, “It’s meta — an anatomy professor teaching anatomy again, that’s so cool. I am also hoping that it will give comfort to students who feel uncomfortable knowing that they’re dissecting donors who didn’t know all the details. [For example] we’re going to bisect your pelvis — that’s the one that gets most people — to know that most people in the room didn’t know that, but here’s someone who knew all the nitty gritty details of what was going to happen, and they chose it anyway. I hope that it would give them comfort.” They are teachers in life and teachers in death.

Image credit: Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine in the public domain.