We have seen our classmates’ faces, memorized each other’s hometowns and politely chuckled at every “fun fact” introduction despite having heard it countless times. Some of us have admitted to writing down random facts about others as we hear them, hoping to review them later and somehow kindle more profound relationships than the pandemic naturally allows. We virtually contact each other later with a random sentiment trying to relate to someone’s favorite sports team or vacation place. Thus far, my classmates seem extremely kind, but I fear that these relationships will be altogether cursory due to a lack of opportunity to truly meet. My class and I are arguably enduring one of the most difficult academic paths, yet we remain strangers to the only people who can relate to our experiences. Sadness creeps in as upperclassmen describe all of the interactive events from when the world was “normal.”

Occasionally, when in-person attendance is required for certain subjects, the days are filled with entertaining, sometimes awkward guesses at everyone’s identity based on eyes and hairstyle. Those that have managed to bond in this virtual environment are seen as intimidating to the rest of the group, as I assume every individual ponders if they are the only outsider remaining. Our isolation is magnified as we miss our families over the holidays due to the danger of infection while traveling. Some of us are even losing loved ones at home due to the pandemic, but we must continue preparing for the next exam, wondering if our situation will ever change.

With our days behind a screen, only about 10% of the class actively participates. We are losing opportunities to practice public speaking or to see a lively lecture with multiple hands raised. It is difficult to remain at home while the physicians we wish to emulate are teaching us clinical applications over Zoom. After a long virtual day, my smartwatch tells me I have 700 steps at 6:00 PM despite my goal of 10,000. Balancing work and life responsibilities is a necessary skill for a well-rounded, mentally healthy physician. Now, our work-life balance is practically gone as class, homework, research and other extracurricular activities morph monotonously together on a computer.

Medicine is too “hands-on” of a field to settle for an entirely online curriculum. Being able to physically examine a patient in primary care, hear arrhythmias in cardiology or break heart-wrenching news in oncology are all skills that must be learned in-person to truly gain an appreciation of what it takes to be a physician. With our current state of virtual education, doctors will receive less training in how to palpate the actual human body, a vital process that gives physicians an initial insight into the health of their patients and eliminates unnecessary labs and costly testing. Research has consistently supported that the physical exam, along with the patient’s history, are the most crucial factors in arriving at a correct diagnosis. Virtual training also creates an immense feeling of distance from patients. In our complex interviewing course, standardized patients act as having suicidal ideation or experiencing domestic violence situations. These are cases that necessitate the privacy and comfort of in-person interaction.

There are historical instances when the need for hands-on, interactive medical education has been emphasized. In the 18th century, medical students would rob graves to obtain bodies needed for dissection. Despite the existence of detailed anatomy textbooks, these students were committing abhorrent acts to facilitate their own discovery within the body. Anatomy courses, and the dissections or prosections involved, are often the first hands-on encounter that medical students have with an open, human body. 3D models or virtual cadavers cannot possibly foster an appreciation for the anatomical variation between donors or real-world applications of anatomical concepts. Walking into a cadaver lab and being introduced to a donor is truly humbling, and I believe crucial to a student’s journey towards physician-hood as they care for their first real patient.

I cannot claim that the pandemic has been entirely void of progress in the medical curriculum. COVID-19 has exposed existing inequities in health care when comparing different races, ethnicities, socioeconomic statuses and other aspects of one’s background that made certain populations more vulnerable to COVID-19. As a result of the heartbreaking statistics, I predict and hope that all medical schools will incorporate information about health disparities into their curriculum, exposing medicine’s shortcomings and better teaching students how to serve patients from all life circumstances. With students aware of these biases in society, they can acknowledge, target and do away with them as future providers. I anxiously await improvements in equitable medical care when COVID finally claims its last life.

Medical education will also carry a newfound emphasis on public health. After a global pandemic, students will gain more awareness of their role in contributing to the health of the nation. Thus, we may find ourselves in an era of physicians who attempt to impact policy and healthcare on a larger scale if medical education capitalizes on this opportunity to prepare them. Students can also receive more exposure to crisis management, should anything similar to an overwhelming virus ever occur again in their career.

In a future where telemedicine is a regular occurrence, students will likely receive training early in their medical careers. They will be experienced in inspecting a patient’s complaints over a camera in addition to in-person techniques. Medical students can also listen to lectures given by people anywhere in the world without needing to travel. Efficiency is enhanced if there is no need to commute to school, and meetings can be scheduled quickly as people tune in from anywhere.

Nonetheless, I believe the necessity to remain in-person outweighs the efficiency of digitalization in many instances. Thus, I believe it will return to a similar structure as pre-pandemic life when COVID subsides. To compromise, the future of medical education could utilize hybrid courses with in-person and online components, a model that was used by many schools before COVID.

One study, conducted with undergraduates before the pandemic, found that online students felt less prepared for the final exam compared to their in-person counterparts and that 89% of students reported a desire for in-person learning time. More recent research on medical students in the United Kingdom during the pandemic discusses how distractions and internet connectivity issues were common with virtual learning. Also concerning, a study evaluating the effectiveness of virtual learning during the pandemic found that there was reduced student engagement, loss of proctored, reliable assessments and an overall negative impact on student well-being and quality of life. These barriers hinder student success and must be corrected before virtual medical education is considered as a long-term option.

I must add: I am appreciative of my school for their caution. On one hand, my health is being prioritized. However, students are here to become care providers on the front lines. It is difficult to be sheltered from nearly every possibility of helping fight a pandemic.

Perhaps I am being idealistic, but I believe courses will proceed in-person at the soonest date possible. At my medical school, physicians tell students they are saddened by the empty hallways that are usually filled with laughter, and they miss getting to know students personally. The students in my class go to campus, masked and sitting socially distanced, to simply be reminded that bigger things exist than the couch in their living room. Although there is an element of convenience to rolling out of bed ten minutes before class starts, I have only heard people long for the alternative.

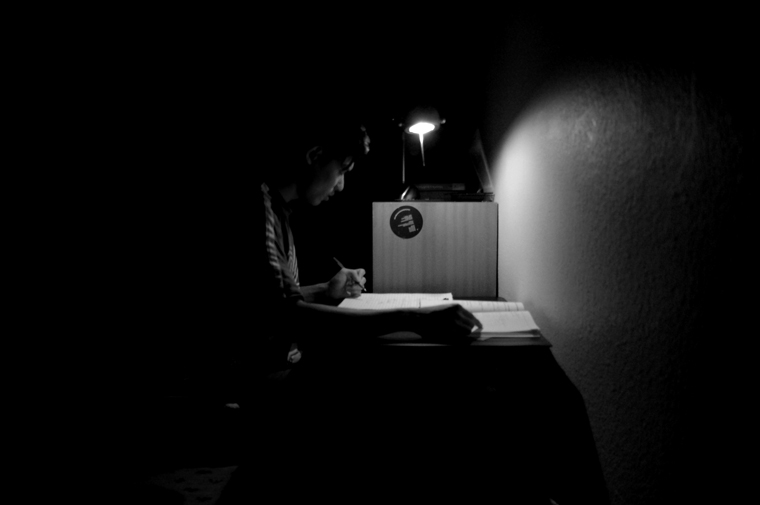

Image credit: Study (CC BY-ND 2.0) by Sani_Flickr