Editor’s note: We are featuring a series of essays by Kate Crofton on anatomy lab. Her essays are based on 27 interviews with medical students, faculty, clinicians and donors.

This is the second installment in the series. Read the introduction to the series here. Read the third part in the series here.

In the golden glow of a fall day, 104 first-year medical students parade out of the medical center carrying boxes of bones to aide our anatomy lab studies. The crates look suspiciously like instrument cases, perhaps the size of an alto saxophone, and it feels absurd to march back to our houses a la The Music Man, knowing all the while that we are bringing real live (well, dead) human skeletons into our living rooms, kitchens, and coat closets. Mine resides propped against a bookshelf in my bedroom. I only open it during daylight hours, and only when absolutely necessary. For the next four months, as we visit classmates in their homes and encounter the subtle black or brown cases they’ve tucked into the corners of their lives, the bone boxes will serve as a reminder of the secret club that we all have newly joined.

A few days later we find ourselves squished into locker rooms, fiddling with combination locks, and dressing in clean cotton scrubs. We ride the elevators up to the fifth floor, hearts thumping, plastering our faces with brave expressions. It’s a milestone moment, our first day of gross anatomy lab. Some of us, including me, are terrified. Others are overwhelmingly excited to learn. We are all nervous. In the hallway we tentatively gown up in yellow plastic smocks and help each other tie them at the back.

A year later, I sit outside of a coffee shop on a warm summer day with a member of my class as she remembers our transition from the hall to the lab. “And then you walk in, and it was just a buzz of activity, which I wasn’t expecting. I was expecting it to be calm and almost somber.” The labs are flourishing with life. Fourth-year students direct us to a wall of gloves and show us how to assemble scalpels, and the professors summon us into a group huddle for a short lecture on the impending dissection.

One of my classmates recalls making the first cut for his group, straight down the back of the donor from the nape of the neck to the small of the back, “I wanted to see if it would be a big moment for me. I was kind of curious to see how it would hit me, if it would hit me.” “Did the clouds part?” I ask him. “No, not really. It was cool, and I was glad that I did it. I did reflect on it, but it wasn’t like some big drastic thing.”

Another student was more tentative during the inaugural lab, “I took a backseat the first day. We had someone in our group who was very eager to do it, and I kind of yielded to them wanting to be very involved. I am now wondering: had I been more actively involved on the first day, would I have not struggled as much? Our donor was quite elderly and had a lot of fat embedded in her muscles. [An instructor] came over and told us ‘your donor probably was not ambulatory near her death. This is what happens when someone is sedentary for a long time and they have a lot of muscle wasting’. So, the first day, we’re systematically taking this person’s body apart, one, and two this person was not in good health before they died. That made the first day even more challenging. This person must have been in pain, they were not able to walk around on their own. Were they just sitting there ready to die? There were just all of these thoughts going through my head, in addition to the run-of-the-mill first day.”

The anatomy lab feels sterile at the outset. There’s a backdrop of white walls, bright lights, fans loudly whirring in the overhead vents, surgical stainless-steel sinks and rows of cadavers, covered in white hospital sheets atop metal tables. Their limbs are rigid and cold, lying on their abdomens, heads wrapped in white hand towels so that we are spared from seeing their faces for the first few weeks. The most startling sensation is the odor. Strong and pervasive, it slowly creeps through the nostrils and whacks you on the forehead, crescendoing to a throbbing formaldehyde-induced headache.

There is no time to linger. The learning commences, and we begin to acclimate. The lab quickly ceases feeling sterile. The lab manual and anatomy atlas, once precisely placed on a metal pivoting stand at the head of the table, are now coated in a brownish residue. Studded with goblets of adipose, their pages stick hopelessly together. The donor, no longer a pristine cadaver, oozes out “fat cheese” and formaldehyde while her right trapezius muscle dangles precariously over the edge of the table, attached just at the shoulder.

Dissecting becomes seductive, the flow of peeling off the skin like the carcass of an orange to reveal juicy flesh covered in a thin but tough film of fascia. Searching, we separate out the bellies of muscles with double-gloved fingers to allow for the aha! discovery of a slippery nerve, a skinny vein or a hardened artery. If you were to pick your head up from a small area of intense focus under dissection and observe the whole room, you might describe it like one student did as “a war zone, or like those pictures of concentration camps when they would collect human remains.” We learn through destruction.

It’s time for a reckoning: is the donor our partner or an obstacle to be overcome? Part of the problem is figuring out what to call the donors. “It felt weird to refer to her by her name at first, once we learned it. Sometimes we used ‘she’ or ‘her,’ or sometimes ‘our donor.’ It felt weird to say, ‘our donor’ because she’s not ours.” We take ownership for our donor, and although the body is not ours, it is our work and care that is evident in each dissection. “Come check out our ilioinguinal nerve!” we exclaim to our neighbors at table twenty-one, really referring to his nerve. The discovery of his anatomy is the fruition of our effort, the well-preserved hand dissection a result of the care we took to wrap it thoroughly in paper towels soaked in Downy April Fresh wetting solution, the mess of torn muscles in the neck a consequence of our confusion. The donor is not an object but also no longer a person. What is the nature of our relationship with the donor?

“I was really grateful, and I definitely learned a lot from her. I guess I like when people say ‘teacher.’ Maybe that’s the closest word that I can think of. I felt a lot of gratitude, but also sadness because she might have been in pain, at least that’s the story I painted. The way her ribs were broken, some people said that she might have been full code. I just imagine what that would have been like for her and her family. In the way that I was personifying her, I did see her as a patient. And then in other ways it’s not like I was doing anything for her. I wasn’t making her feel more comfortable or anything, so I can’t call her my patient. So maybe the teacher part would work?”

It is a balancing act to cut into the dead body but also remember and honor the person, who we never knew, to “try to remember that they were people with lives, hopes and dreams, and they were not this vulnerable for their whole lives. This is as vulnerable as it gets.”

The day that we dissect the hands, my partner and I are paralyzed at the beginning of the lab. The hands are so personal; they tell our donor’s life story. To see the tightly laced muscles in the palm, one of us is going to have to pry his stiff fingers back as the other removes the sturdy, calloused skin with a scalpel. A teaching assistant comes over to help us, and half crying, half laughing, we ask him to give us a few minutes. When he returns after a generous lap around the room, we are taking turns: one holding, one cutting. I have pushed aside many of my feelings about the matter and am instead focused on the muscles. You do what you must to perform the “difficult” dissections. I noticed that it came more easily to some of my classmates.

“I pretty quickly did a good job of compartmentalizing and intellectualizing my relationship with my donor. I very much value her gift and what I learned from her. I know that people in my group and others in our lab felt more emotions while dissecting. The first day or two was certainly weird, but very quickly it became pretty normal-feeling for me. It just wasn’t all that hard to dissect those things [hands, face], emotionally. I’ve wondered what that means about me, and I don’t know. I haven’t come to a conclusion; I’m not sure that I will.”

We find ourselves committing unthinkably desensitized acts. “It wasn’t that long of a time that passed before I realized that I was leaning on my donor. The face was covered, and I forgot that there was a face there. Sometimes just to reach what we needed to do, I would lean on the face and then suddenly remember: this is a person. It would hit me.”

It hits us when the dissection feels like an invasion of the donor’s personhood. “The dissection of the face was really hard. What actually helped most during that lab, because we were all having trouble cutting around the eye, and it felt like we were violating something, [the anatomy instructor] came over and she said ‘I’ve been doing this for [decades], and there are always labs for each one of us professors that we still find difficult, and this is it for me.’ Just her admission of that, and taking a second to say ‘yes, this is hard, it’s still hard’, that helped. It was a good reminder that there are a lot of feelings that we project onto our donors.”

We ask ourselves, “Am I still a good person?”, worrying that anatomy lab has robbed us of our former morality. We are warned that we will have to transect the abdomen and bisect the pelvis to study the genitourinary system, but we have no idea that it will change us. At the end of the dissection, the body feebly lies on the table in three severed chunks: the left leg, the right leg and the trunk. This dissection is distressing to many of us, including one student who sought consolation from her parents, “I told them about the cutting the body in half … and then I looked at them and asked, ‘Do you see me differently now that I told you that I did that?’ I don’t remember their exact response, but it was comforting. I do remember my stepdad asking, ‘Is this something you can’t learn from a book?’ I don’t know if he was actually asking me what I really thought or if he already kind of knew the answer and was trying to make me feel better, because the answer was no — you can’t learn it from a book. You really, really can’t.”

We rationalize, we justify, we repress. I am a timid dissector at table 22, but I want to participate and learn. I face a conundrum: I don’t want to dissect, but if my hands aren’t touching the structures, it is nearly impossible to be engaged in the lesson. After playing a supporting role during several big moments (my bolder lab partners removed the heart, disconnected the lungs from the thoracic cage and broke open the vertebral column to reveal the spinal cord), I am starting to warm up to lab. I have become more comfortable blunt dissecting fascia with my gloved fingers and removing the skin with a scalpel. I tell myself that I should participate more fully even when I am scared, because I don’t want to waste the opportunity to learn. And so, I am the one who halves our cadaver’s head with a handsaw as my lab mates grab his cheeks, holding him still. I am not the only one pushing through uneasiness.

“I decided for myself that even the most invasive labs are out of respect. If you only do the ‘easy ones’ then you aren’t really learning that much.”

“In medicine, when you’re in the room, you have to forget about your feelings and push through it. If something is bothering you enough that it’s past your shift or your time in lab, then you deal with it outside. I had a couple moments where I thought ‘is this really the right thing to do, am I supposed to be here? Do I trust that what I am about to do to this person’s body is okay?’ Those moments took less and less time to get through. It was a couple seconds at the beginning and a fraction of a second by the end of the course. I just pushed through any discomfort.”

“It was odd how much I could repress the idea that this body I was about to mutilate once held a soul with a life as vivid as mine. Each time I entered lab throughout the semester, I had the same slight tinge of apprehension. And each time I acclimated to the point that I wondered if I would ever have the same sensitivity I entered medical school with.”

One of my classmates says that he is helped by the quote, “Worrying is like a rocking chair. It will give you something to do but won’t get you anywhere.” I am rocking in place, unable to shrug off the worry that I am losing my sense of self.

And then we become curious. In discovering the absence of a uterus or the presence of a bulky tumor, broken ribs or mauve toenail polish, we want to know more about who the person was in life. Several weeks into the semester we learn the donor’s name, age, cause of death and occupation, but there is so much left unknown. And so, we extrapolate.

A professor describes an experience early in her career witnessing students construct a narrative for their donor after finding a butterfly tattoo just above an old chemo port on her chest, “The students decided that this individual had cancer and then sort of as an affirmation of life, got a tattoo. I’m thinking to myself: you don’t know the order of events. There was a part of me that thought it was disrespectful to potentially disregard whatever reality there had been for that donor’s life. But then I kind of reworked that thought and decided that maybe it’s okay for this butterfly tattoo to have a different meaning for the students now that the donor is dead. Isn’t that kind of an analogy for everything that we do in anatomy lab? You have all these structures that move you around, pump your blood, and breathe your air, and now they’re not doing that anymore. Now they’re learning tools for medical students. Maybe it’s okay for the butterfly tattoo to take on a new meaning for the students if it helps them to relate to this donor, be more human about this in their practice, and go on and be better.”

A student explains that while it was helpful to create a story in her head to understand why her donor might have given her body, it also felt wrong. “Giving them a name almost feels like you are ignoring the person who decided to give you the body. I don’t believe in an afterlife, and I don’t believe in religion, and so I don’t think that there is a spirit there. I still think that it’s important, as you are interacting with someone’s body, that that was at one point that person’s body. They lived in it and knowing the truth of their story can both help you understand the body that’s in front of you but also pays respect to that choice to let someone cut you up and learn from you. In the same way, once in clinic I said, ‘Mister’ and [the patient] corrected me and said, ‘No, it’s Doctor.’ We take a lot of pride in our identity and what we’ve achieved as human beings. If you take that identity away by imposing a fictitious story on someone, you risk ignoring who they were.”

The stories that we craft for our donors do not always withstand the tests of time and dissection. I will never forget prying open my donor’s hands and discovering that he was missing a large chunk of a finger. A classmate recounts a poignant experience with her donor, “The day that we cut her pelvis in half to find no female parts … she did have a big incision going this way [points horizontally across abdomen], and we thought, ‘oh, C-section, she’s had babies,’ which for me was a cool thing — this body gave life to other bodies. To have had that schema in your head and later find out that it’s gone was on the one hand, kind of sad. I don’t know if people who’ve had their reproductive parts removed grieve the loss of those or if they are happy that they are gone. Maybe they had some horrible tumor, and maybe they just wanted to get rid of it? Maybe they have a more complex relationship with that part of their body, and they have mixed feelings about it? I guess it left me wanting to know more about why. Or what were her feelings about it?

Also, it was tough because the professor in our room wanted us to be able to learn from the female reproductive anatomy, but neither of the female donors in our room had it. He was in his educator mindset of wanting us to see it, and he was a little disappointed when neither one had it. It was hard for me because on the one hand, yeah, it’s a little disappointing that we’re not going to be able to see what we needed to see, but on the other hand we got to learn a lot from the rest of her. It’s not really her fault, I’m sure, that this is gone. I had this feeling of, and I don’t know if ‘felt’ is the right word, but it felt empty. The uterus was gone, she had had her ovaries removed. There was nothing there. This isn’t what it is supposed to look like. And then I had to think about ‘supposed to’ — is that a value judgment? Does that place some phenotypes better than others? So that was hard. Having bisected the pelvis and seeing that didn’t make me feel like it was a waste to have done it or that it was wrong to have done it. It was thought provoking I guess, more than anything.”

There are other challenges, too. To start, the obvious challenge of doing a good job with the dissection. The goal is to be as efficient as possible, remove the connective tissue and fat and quickly find your way to the muscles, ligaments, tendons, bones, vessels and nerves. There is a danger of going too fast, though, “I ripped muscles right off … I was blunt dissecting and ripped something by accident doing that. And I didn’t feel anything, that was the problem — I didn’t feel it until it was too late. I was struck by how tough the skin and integument were. That was literally all my strength yanking on the person, skinning the person.”

A subtler challenge is remembering to be grateful for the privilege. “You go upstairs, get your scrubs, change, put your gloves on … do the whole thing, ask questions, clean your table … It just became routine, and I was not as intentionally grateful for the opportunity as it went on. I guess it is kind of understandable because we spend so much time in there, and once you leave, you’re going to go study and do whatever it is you have to do with your life.” I ask a classmate whether he had any rituals in lab. Other students have expressed the importance of cleansing their donor at the end of each lab and dressing him in a clean sheet, journaling or writing periodic letters to their donor or going to lab after an exam to reflect instead of to study. But he answers, “No, and it’s a good way of articulating how stressed I was. I had routines, not rituals. Even ritual things can become routine depending on how they’re received.”

Most ominous, there’s the challenge of maintaining the relationship between student and donor. I find this easiest at the end of the course when we are dissecting the lower extremity. The leg is nearly a recapitulation of the arm, the muscles are big, and there is enough room for all four teammates to work and see at once. I feel internal space to direct loving-kindness toward our donor. My relationship with him is most tenuous during several tedious dissections of the head and neck. The dissection of the temporal region allots us two hours to poke around in a claustrophobic window from the cheek to the ear, searching for teensy tiny nerves which allow one to taste and chew. By the end of the lab I don’t know up from down and haven’t seen most of the structures listed in the lab manual. I am frustrated at myself, at my lab group, and at my donor.

It helps now to know that I was not alone in my feelings. A classmate admits, “Our donor was an elderly woman who didn’t necessarily look like it does in the book. And I started getting feelings of anger and frustration at our donor. And then I’d think to myself ‘wow, I feel horrible that I feel that way,’ and then try to disengage which was also not productive.” Ultimately, the frustration is only a temporary setback and we keep learning.

As the partnerships develop between us and our donors, we consider whether we might choose to be donors someday. “I will just have to decide if I am comfortable handing my body over to strangers in my death. I know I will have vacated it, but still I feel an attachment to this body, and it is a strange thing to contemplate.”

“I’d be open to donating. The thing I’d be more uncomfortable about is having someone I know and love donate.”

“I’d always wanted to be an organ donor. Now, I very strongly feel that I’d like to be an anatomical donor and pass on the gift that I was given as a medical student.”

We live, breathe and dream anatomy lab — literally. Peaceful dreams of floating spinal cords, suprascapular nerves from the anterior aspect, the fimbriae of a uterus, the chorda tympani. Nightmares too — I awake in a disoriented horror one morning after performing a live laminectomy on my mother.

A classmate dreamed, “My wife was speaking to me and at least her neck, if not more of her, was vivisected cleanly to the muscles. She asked me what a certain muscle in her neck did, and I told her I didn’t remember exactly, but that I didn’t think it was that important, at which point she grabbed the muscle and sloughed it off her neck. I tried to stop her, but she did it before I could intervene. Afterward, she was unable to speak, and I woke up confused and disturbed and had to make sure she was okay.”

Visions of anatomy not only come during dreams, but also during the daytime. Multiple students described looking at friends, family or strangers, and thinking past their skin to their muscles and bones. “I noticed that over time if I’d start to let my mind slip when I was talking to someone, suddenly their skin would fall off and I would imagine their head split in half and I would look into their nares.” We can’t stop studying anatomy.

Anatomy lab has become a dividing line in our lives. We will never think about the body in the same way, because our donors have given us a detailed map. “Let’s say I have a transient pain in my abdomen — I used to think of it generally as intestinal pain; now I can pinpoint where the pain probably is coming from and what’s likely causing it, because I can easily see where the different parts of my intestines and my other abdominal organs should generally be, their approximate size, which are more anterior or posterior, et cetera. I often think about the body in much more internal, anatomical terms than I used to, and I can’t believe that this isn’t a common experience that everyone shares.”

We memorize thousands of body parts, and we learn other lessons too, intangible ones. “It made me more confident. I constantly have imposter syndrome where I feel one of these days people are going to turn on a light switch and go, ‘huh, why is she here?’ I’ve had that for as long as I can remember. It’s the same with medical school—there’s no way I’m as smart as these people, I don’t really deserve a place here. But once I graduated from anatomy lab it felt more like, no, I do deserve a place here. I can process these emotions, and I can use them in a constructive way. I know a lot about the human body, and I know a lot about how I think about some of the ethical things in medicine.”

“There’s an endurance that you start developing mentally and physically. Being able to assimilate information quicker — there’s a skill in it. I’ve never reached my limit in understanding before. I’ve always been able to, within the period of a class, grasp material almost completely. My go-to was to just work lots and lots and lots of hours until I knew every possible thing that they could ask on a test. [In medical school] I couldn’t do that. No matter how hard I tried, I kept getting frequently an average or below-average grade. I remember something [my advisory dean] said to me: I asked her, ‘Do you think I’m going to be a competent doctor?’ And she said, ‘Competency is knowing what you don’t know.’”

I speak to several fourth-year medical students who returned to the anatomy lab as teaching assistants and ask them how anatomy lab prepared them for their clinical clerkships. “For many students, [anatomy lab is] the first experience that they have with seeing somebody who’s dead, the first experience that they have with cutting into a body. That really helps to start the transition to being able to do this more frequently.” “Having support from my classmates was incredibly important during anatomy lab. We could talk about how challenging it was to do some of the dissections and how emotionally taxing it was. That’s something that really carried over into [the latter years of medical school.]”

It is a team building exercise, most certainly, to properly disassemble a cadaver. Even flipping the rigid body over in anticipation of moving from the study of the back to the front requires all four tablemates to cooperate. “[Before medical school,] I’d worked pretty closely in a few teams but not in the same sort of way [as anatomy lab], and not physically close, having to communicate certain directions in such a specific task-oriented way. That was something I really enjoyed, and I really came to appreciate my teammates for the qualities they brought to the table — literally to the table.”

Some tables are more cohesive than others, a symbiotic organism formed from sixteen living upper and lower limbs. Others are disjointed, a flailing mess of tangled arms and legs. A first-year student reflects, “I learned how to stand up for myself a bit because if I didn’t jump in the assumption was made after the first few labs that I just didn’t want to do a lot of the dissecting. I had to assert myself and go ‘hey, can I have a turn?’ or ‘how about you finish this part and then I’ll do the next part.’ Because I also didn’t want to ruin the groove of the team, and I didn’t want to slow us down.”

A medical humanities instructor recalls observing a shift in one lab group. For the first part of the semester, “They weren’t dysfunctional, they just weren’t working optimally as a team; maybe you could describe them as four individual learners. Then I noticed a difference, and I asked them why, and one of the team members had had everybody over for dinner.” We learn to accommodate our individual group members and negotiate our differences (admittedly some groups do it better than others). One student excitedly tells me that she’s planning with live with one of her lab partners next year. Another recalls with sadness the discomfort of having to report a lab mate for an academic dishonesty concern. Even during the stressful moments (and there are plenty) a special sweetness holds us together. We are bonded by all doing this bizarre, difficult thing and coming out the other side.

Then it all ends as suddenly as it began. We have dissected all twenty-six donors back to front, head to toe, and it is time to return the bone boxes, throw out our formaldehyde-soaked scrubs and say goodbye. The professors set up the laboratory for the final anatomy practical, sticking black and yellow pins into the donors. We silently rotate through the tables each time the buzzer sounds, scribbling down the names of the tagged structures. The final exam is the setting for the last two minutes that we will spend with our donors.

“There were two goodbyes for me. One was to my lab group — we developed a nice relationship, and they became people I relied on. Then there is the goodbye to the experience. Wrapped up in that was saying goodbye to our cadaver and saying goodbye to the room and saying goodbye to the faculty. I’m not sure I did a great job of doing that. This is the case with so many things in medical school, fortunately or unfortunately, but my last experience in the anatomy room was taking an exam.”

“I remember it was during the test that it hit me — this was going to be the last time that I saw my donor. I remember that I knew exactly what was going to be tagged because [one anatomy instructor] loved it so much. We were the only ones who had that structure. I had a few minutes left over to look at my person after I wrote my answers down. I just looked, just kind of took it in. Up until that moment I was just so into studying I didn’t let myself process it. I told myself ‘that’s it, the buzzer is going to sound, and that’s going to be my last experience with my person.’ And then we just moved on.”

“I don’t remember too many details about how I said goodbye to my donor, but I do remember that my last day in the anatomy lab was a special and sad day for me because I knew that I would miss being in the cadaver lab and doing dissections. I remember looking at the body one last time and just thinking, thank you.”

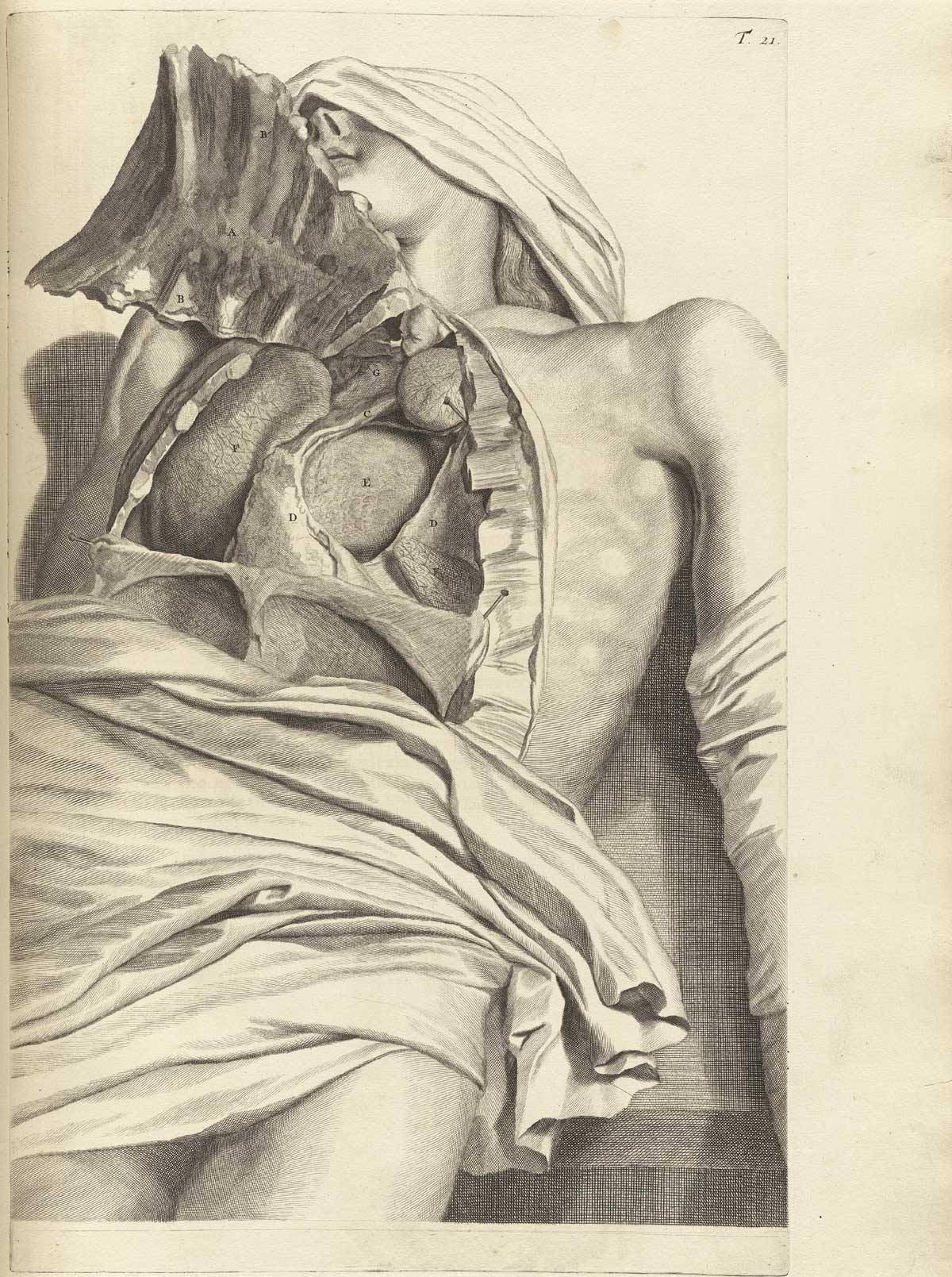

Image credit: Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine in the public domain.