Eric Bethea (2 Posts)

Eric Bethea (2 Posts)Contributing Writer

Emory University School of Medicine

Eric Bethea is a fourth-year medical student at Emory University School of Medicine class of 2021. He graduated from the University of South Carolina in 2016 with a Bachelor of Science in economics. Before entering medical school, he spent a year serving with AmeriCorps in Jacksonville, FL. He is looking forward to writing about topics that don't often come up in medical school. In his free time, Eric enjoys running, basketball, movies, and cooking with his favorite crockpot.

And with scientific advancements came cures and treatments that the healers of antiquity could have never imagined. However, these advances came at the cost of appreciating a holistic approach to health. How pitiful is it when a profession which was once completely focused on healing the whole person must now devote entire conferences and countless seminars to finding ways of injecting that back into both its practitioners and the people they serve?

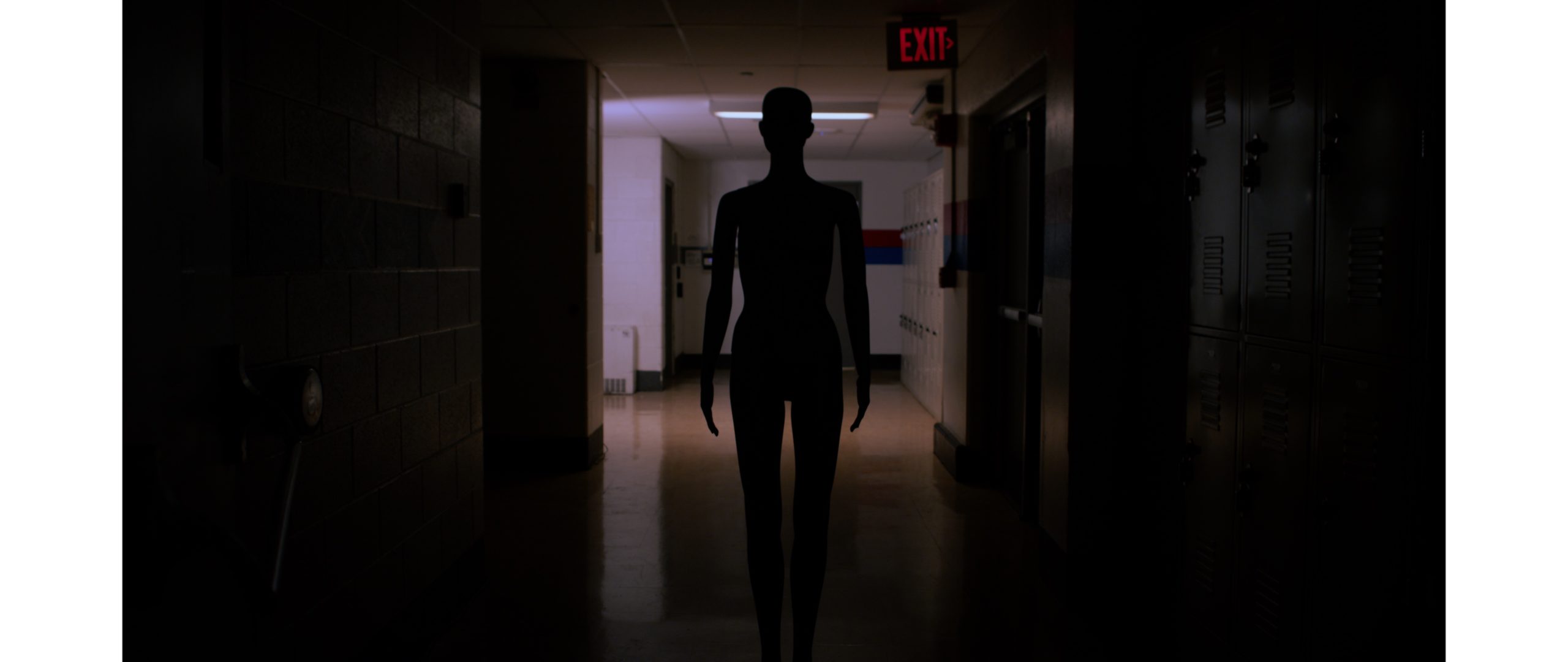

A first-year medical student’s stress and anxiety begin to take physical form as she navigates her first year of medical school.

You don’t have to sit in silence and painfully nod along with an attending’s racist, misogynistic lectures because you’re their medical student. You don’t need to pick the skin off your cuticles to stop yourself from replying. You don’t need to learn how to hide your grimaces behind your mask because you know you’ll have to listen to them attack your identity for the next several weeks.

While it is easy to feel stuck and unhappy in this current life-box, I recognize that we must take a few deep breaths and understand that this too shall pass. And that this did pass for all the physicians before us and will pass for all the physicians after us. And we will all get past this together.

I was anxious because I was used to moving at such a fast pace that slamming on the breaks gave me whiplash. I was desperate for things to do because I had forgotten how to slow down and relax — how to just be. Slowly, I began to see the opportunity that quarantine had presented me with.

A medical student, to whom I will refer as X, posted on their social media page they were going to kill themselves. Their letter was direct, raw and, as many suicide notes tend to be, apologetic. They explained they felt they no longer had the strength to keep fighting; it was simply “time for them to go.”

Interviewers who ask these questions in a professional setting typically consider these issues to be academic — purely topics for discussion that might provide useful insight into the way the applicant views the world. But for applicants who have been affected, these issues are not merely academic and their discussion can invoke significant emotional turmoil. So before we continue to tacitly accept this shift in interviewing, it is important to consider its purpose and impact on those being interviewed.

It feels preemptive to discuss emergence while sitting in the living room where I’ve spent 15 hours a day for the past month — bradycardic afternoons mirroring the day prior. Yet each day the sun emerges, and we along with it, venturing out onto balconies and porches. As medical students, we take our pro re nata walks and remember to cross the street so our paths don’t intersect those of our neighbors.

The world is quarantined, but we have learned to be human again. Rather than tirelessly working or studying, we are forced to engage with one another in meaningful ways. We find novel alternatives to maintain relationships with those who mean the most to us during this daunting time with no foreseeable end.

I am okay being alone; it’s not hard to do. / For other people, they can’t do it as if they were left scarred anew. / The trick is to keep your mind busy.

Back in late March, I was a medical student in D.C. studying for exams. Today, I am a 23-year-old living with my parents again. Despite being in school 5+ hours away, my bedroom in upstate New York has become my new classroom. Being at home has its perks: I get food from my mom again, and I can wear pajamas all day if I wanted to (not that I actually do that). However, there are many things that don’t feel right about being a medical student who has no connection to the medical world right now.

After our conversation, I’ve been thinking a lot about creating community. As students of color, especially in areas with low diversity, we create our communities of allies with other students of color or students who are open-minded and willing to learn. For students who come from places with established diversity, the transition to creating communities of their own can be a challenge.

Archana Bharadwaj (6 Posts)

Archana Bharadwaj (6 Posts)Contributing Writer

Central Michigan University College of Medicine

Archana Bharadwaj is a second-year medical student at Central Michigan University College of Medicine in Mount Pleasant, Michigan. In 2013, she earned her Bachelor's of Science with a major in Biopsychology, Cognition, and Neuroscience and a minor in Gender and Health from the University of Michigan. She went on to earn her Master's in Public Health in Health Behavior and Health Education with a specialization in Health Communications from the University of Michigan in 2016. Outside of school, she is an avid foodie with a penchant for traveling. After graduating medical school, Archana would like to a pursue a career in Anesthesiology.

In Color

In this column, I will explore the unique challenges of training as a provider of color and offer solutions for improving diversity and inclusion in medicine. Through conversations with colleagues of color, including premedical students, medical students in training, and residents, I hope to create a community where we can learn from one another, cultivate allyhood, and find support in our professional journeys.